The subway breakdown: Fixable?

November 4, 2019

Ilana Marengo stands on the platform, scrolling through Instagram and waiting for the G train to arrive. This isn’t a new problem, she explains. “It’s a long wait every day.” The trains have been like this for years.

The station starts to fill up with impatient people, muttering under their breath about their busy lives and how crappy the trains are in the morning. Some people pace back and forth, occasionally peering down the tracks, while others congregate by the wooden seats, but nobody looks surprised. A clock showing the time announces that the G train will arrive in two minutes. An announcement comes on, bleakly reminding riders that if they see something, they should say something. No one pays much attention.

When the train finally rushes by, everyone lets out a sigh. It’s packed. The people who are closest to the doors squeeze on, while the rest – including Ilana – remain on the platform. “I can’t be late. Colleges look at absences,” she says worriedly.

For many people, taking the subway is their only option; they don’t have the resources to get to school in a car or bus. When the trains break down, they’re stuck. This is why it’s imperative to have a functioning, reliable system. This, however, rarely happens.

The MTA system is breaking down because of climate change, money issues, and new policies. Many commuters and workers alike feel despondent, but through a 54 billion dollar plan, the future of the NYC subways are looking up. This system would transform ridership and service for millions of commuters around the city.

“The subways are really bad,” says Nia Hurley, an iSchool freshman. “It feels like I can’t ride one without a delay. But from what you’ve told me and what I’ve seen, it’s getting better.”

DELAYS IN THE SUBWAYS

In 2017, Andy Byford was hired as a desperate attempt to fix the mass cycle of delays. Most students agree with this. Before then, delays were a common occurrence. In a response to an online survey, 92.8 percent of responders said they ride the trains every day, with 85.4 percent saying that they need repair. This broken-down state leads to frustration and a lack of want to ride the subway at all.

CUNY anthropologist and climate activist Naomi Schiller comments on this, saying “I live a mile away from the F train, so I use a lot of busses. But the busses are really slow… and I’d much prefer riding public transportation than sitting in a traffic jam, but I don’t often because it’s not reliable. I know I have only a certain amount of time to pick up my kids, and I can’t risk taking the subways so often if it doesn’t get me there on time.”

This is the case for a lot of people. The worse the subways get, the more angry the commuters become. Some people, like Mr. Jones, an English teacher at the NYC iSchool, have big delays, “One time, on a weekend, I was going to Brooklyn to see a play, but it [the train] was so delayed that I ended up getting off the train and not going. I was going to miss the first act completely,” while others, such as Ilana Marengo, experience relatively short delays on the regular.

These delays aren’t coming from nowhere and happen consecutively. 54 % of responders say that their trains are delayed. Many factors control the subways and cause delays. One such factor is overcrowding. The more people packed onto the train, the slower the doors close and the longer it takes a train to move. As The Atlantic stated in 2017, “Ridership exceeded 1.7 billion last year, and broke records set in 1948. These days, overcrowding is the reason for about one-third of the system’s delays any given month, the MTA says.”

A huge, and widely recognized issue within the subway system- causing delays- are malfunctioning signals and new rules regarding track work, which The New York Times has addressed. Signals are things that look like traffic lights that you can see if you look down the platform. Their purpose is to direct traffic and keep trains within their speed limits. When correctly functioning, if the train passes the speed level, emergency brakes are automatically activated, ensuring safety. This would work if signals operated properly, but malfunctioning signals cause trains to be stopped even if theyŕe going under the speed limit, causing the tracks to get slowed down by unwanted emergency.

Chris Dooling, a train operator that works on the N line, says, experiences signal problems “every day.” “Sometimes if you’re lucky, you see the signal pass from red to green before you go through it. Other times, I could have passed the signal with my train car, but there are 9 more cars on the train that could get tripped.”

Because a lot of the time you can’t tell if a signal is faulty until you go through it, train conductors are going 10 or 15 miles below the speed limit in order to avoid getting stopped. If the signal is tripped, not only is the one train stopped, but all the trains behind it are backed up as well. In addition, when you hit a malfunctioning signal you have to do a lot of work.

As Dooling says, “I would have to call control on my radio to inform them and go downtown to the tracks and investigate the cause…which causes a long delay.”

While some rules were also instituted to protect track workers from injury, it ends up slowing things down. The MTA system made it so that when people were doing track work, they had a longer, more careful setup process because rushed work was causing track malfunctions. They also said that trains have “slow zones,” where if one track is affected by work, the trains on the next tracks have to go thirty miles below the speed zone, even though they’re not going through the working zone.

The New York Times says, “With the new rules, trains traveling near track work must go at less than 10 m.p.h. — 30 m.p.h. slower than the system-wide speed limit. Even far from track work, the slow zones create bottlenecks and reduce the number of trains able to run.”

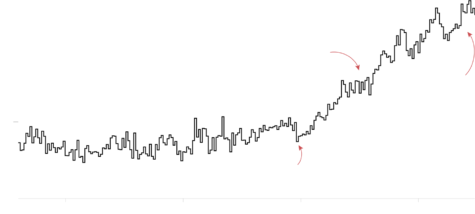

2005 2010 2015

Delays have increased drastically in a ten year period, increasing every time a new policy was added (red arrows.)

The train infrastructure is also very old and outdated. Examples of this are both the tin cars and the controls. The A or C train, for example, is famous for being an old train, with a tin car and no stop board. The Atlantic says that in many trains, “In fact, it’s so old that the MTA can no longer buy replacement parts from the manufacturer; it has to refurbish them itself. Some of the controls for the interlockings are originals from the 30s.” Because these are so old, it takes longer to turn on and run, leading to delays.

Not only does this slow things down, but it can also be dangerous. “Much of the wiring is still insulated with cloth, instead of rubber; ten years ago the entire Chambers Street interlocking caught fire.”

Despite these new policies being ineffective and slow, they were introduced to help, not harm. The signals were to protect the operators and commuters from crashing due to high speeds, and the trackwork rule to make sure the tracks were both set up more carefully, and so that workers could have less risk. Most people don’t know this and think the worst about them.

As Mr. Jones says, “I think what might be important is that that message be better conveyed to commuters, because I think when people hear that, they become more patient and understanding, but I think anyone’s going to make the leap, and assume that a delay means inefficiency and disorganization in the system.”

Another big issue many commuters have with the subways is the cleanliness. Rat sightings are common, and a variety of unidentified substances can be found on seats and floors. Why is it that other developed countries old, almost archaic subways function more smoothly, reliably, and with more cleanliness than New York? There’s not a real answer.

One prime example of this is Canada. The platforms and train cars are clean, they arrive on time, and no one expects delays. Rachel Lindheim grew up in Toronto, Ontario, taking the subways to get places for 18 years. “First of all, subways run a lot more smoothly in Toronto,” she says. “There were never any crazy delays there, whereas I feel like riding the subway in New York there’s a delay almost every day somewhere. I would also say that the distance between stops is a lot shorter. What I noticed when I moved here, especially in going to Manhattan from Queens, is that the stops are so far apart. Because the stops were shorter, it always felt a lot more efficient, and quicker. Andy Byford worked on the Toronto trains from 2011 to 2017, and even won the “Outstanding Transit System of the Year.” As Lindheim wonders, “How is it that he was able to transform the Canadian transit system, but not New York?”

Though Byford isn’t having a ton of current success, before they hired Andy Byford in 2017, the train service was plummeting. According to the New York Times, the delays peaked in 2015, with the delays for track maintenance going up ten percent in four years, with the same amount of work being done. Once Byford was hired, subways got slightly better. Slightly.

Mr. Jones agrees. “I think things have gotten better under his [Byford’s] leadership. Definitely, before that, things were getting very bad, there were some days at school where I began class with 30 or 40 percent of the students. You obviously can’t blame all of those students for being late. So, I think it’s gotten better in the short term, but with massive ebbs and flows in the quality.”

CLIMATE CHANGE IS CAUSING BREAKDOWNS

One ebb in the quality of subways is climate change and natural disasters. As the outside world deteriorates, so does the infrastructure, causing major damage that is still being worked on today. Hurricane Sandy wreaked havoc on the trains. It actually flooded the subways, PBS and the Daily News said. Tt’s taken billions of dollars to repair and revamp for future storms, and the MTA even put in a sea wall to stop the A-line in Rockaway from flooding. In 2007, new stations were built 10 feet above the established flood line, but as carbon emissions increased, so did the sea level.

Escalator submerged in water at South Ferry station

MTA working on rebuilding South Ferry station

Despite climate change hurting the subway, people need to ride it for the same reason. As Curbed NY states, “ Despite New York’s extensive public transportation system, this is roughly in line with the national average, where transportation accounts for 28.5 percent of greenhouse emissions. As New York’s population grows, this shift is almost certainly a direct result of poor service; the fact that weekend ridership is plummeting by 4.7 percent year over year.” Because the subways are in such disarray, people tend to turn more to Ubers or cars, perpetuating this cycle of carbon emission.

If people want to make an impact on global warming and do their part as citizens, they should rely on the subways for transportation. As Naomi Schiller says, “Oh absolutely, I totally think that’s possible. [shifting from cars to the subway] I mean, there’s always going to be a small group of people that needs cars, … but I think the vast majority of us if there was accessible, reliable, quick, affordable if not free public transportation, that people would use it. And it should be funded. If it’s heavily subsidized, or even free, a lot more people would be incentivized to take it.”

FAST FORWARD PLAN

Despite the subways fluctuating, Andy Byford introduced a 54 billion dollar plan to revamp the subways. This is called “The Fast Forward Plan,” and it hopes to modernize NYC transit in ten years by installing new signals, power and modernized interlockings on many new lines, as well as a lot of station work. According to the MTA, they are doing in 10 years what is scheduled to do in 40.

The Fast Forward Plan, like our growing society, will be very technology-based, increasing efficiency and reliability.

One main part of this impending modernization is CBTC or Command-Based Train Control. This is basically a signaling system, where the system can determine an accurate location of the train without the help of track circuits or operators. CBTC is also supposed to help with collision avoidance, over-speed protection, and miscellaneous protection. May people hail this as a good thing thinking that safety would increase.

Others, such as Chris Dooling, do not. “I think a lot of repairs need to be made to the system. It’s necessary, but I’m skeptical. I don’t like that they’re putting on CBTC. Trains with this go into an emergency all the time. If one thing goes wrong and one computer shuts down, the trains on CBTc goes into emergency.” Like the signals, something introduced to the trains intended for safety can malfunction, creating even more backup.

CBTC is being implemented as quickly as possible, say that MTA. They have to install this without completely shutting down the subways, so there might be an increase in delays on the weekends or nights, due to construction and implementation.

CBTC is also doing something that other conductors already do. “I worry about the elimination of operators jobs,” Dooling says. A train operator’s job is not only to drive the train from station to station, but to communicate with the railroad control center, so putting in CBTC could potentially put a lot of people out of jobs- an ever-growing concern in today’s economy. On the other hand, however, if worked correctly, Command Based Train Control can reduce maintenance funds, allowing the MTA to funnel money into a different part of the subways. In addition, CBTC sends the location of the train to the command center, helping pedestrians know what time the train is coming.

Another part of the Fast Forward Plan is repairing and cleaning many stations and even adding new ones. When asked what they would change if they could change one thing about the New York subways, most responders to an anonymous survey said cleanliness.

Kim Ciaccia, a resident of Bedstuy, Brooklyn agrees. “At my train station, at Utica ave t on the A-line, I don’t feel like I’ve ever seen a single person cleaning, I don’t feel like the trains are cleaned enough at the end of the day.” So does the MTA. They notice that mobile wash units and staff aren’t doing enough, and in January 2019, they planned to spend 9.5 million dollars on a deep cleaning of the stations. They also are ordering things such as vacuum cars to help clean the crumbling tracks and walls, says the New Yorker.

The digital part of the plan was shown through new train controls and CBTC, but also through devices outside of the train. One project already implemented in many stations is the electronic screens on the platform, displaying arrival times for trains. Before this, you had to wait however long it took, not knowing how soon you could ride, but with these, you know exactly how long it will be before a train arrives, so if it’s taking too long, you can switch stations or take an uber.

People such as Rachel Lindheim appreciates these screens: “One positive thing that I’ve noticed in New York trains is the electronic screen on the platform that shows the arrival times. They didn’t have those when I moved to New York in 2010, and I find it’s very helpful when you know how long it will take. Even if it’s a ten-minute wait, at least you know how long it will take.”

MONEY ISSUES + GOVERNMENT FIGHTS

For a while, the question wasn’t about the plan, it was about the budget. A lot of people were arguing about where the money would come from. The state and city funds the4 New York subway system, as well as being controlled by the governors. Governors and Mayors usually disagree on how to control it- though it is run by Governor Cuomo, it is very costly and wins very little votes. Governor Cuomo and Mayor De Blasio had been arguing about this.

The New Yorker sums it up. “Cuomo believes that the city is not contributing enough to the transit budget. De Blasio points out that it is paying two and a half billion dollars toward the current five-year capital improvement plan. He also argues that city residents already pay the greater share of the M.T.A.’s bills, through fares and state taxes.”

Not only, however, are Cuomo and Deblasio fighting, but so is Cuomo and Andy Byford himself. Politico broke the story and said that Andy Byford tried to resign from the MTA, citing Cuomo as his reason. Governor Cuomo wants to partake in service cuts all through the MTA system, and having Byford deal with them is distracting him from his job of renovating the system. He also is distracted because of conferences outside of his job that he has to organize.

Many people were in extreme crisis and concern about this news, and officials spent about a week talking him down. Byford finally released a press statement, given by the MTA saying “I’m not going anywhere and I remain laser-focused on improving day-to-day service for millions of New Yorkers and delivering a transformed transit network. The historic $51 billion capital plan provides a golden opportunity to further transform the subway and bus network — with unprecedented investments in accessibility — and my team and I are totally focused on achieving that. The Governor and I are on exactly the same page about the need to dramatically improve the transit system in New York and we now have the plan and the funding to do that.”

Most of the funding mentioned is being paid for through federal money, state and city funds, and bonds from the MTA. There is, however, a taxpayer role in this. The MTA has instituted several taxes. One of these is congestion pricing – where drivers get charged for entering heavily trafficked zones, though it has yet to be passed in legislature. Another is the progressive housing tax, where homes worth $1 million and over get taxed. Curbed NY says that this is expected to make 365 million dollars per year, which could be very beneficial to the subways.

Though most people agree that this plan is necessary, many people question the worth of the money. Over the years, the plan has grown from 20 billion dollars to the 54 billion it is now. For example, an average American makes around 36,000 a year. According to USA Today, people from ages 35-44 pay 13,000 in just federal, state, and local taxes per year, not to mention bills. Paying taxes for the new subway plan on top of that can sound a bit excessive.

Some people, however, disagree with this.

Kim Ciaccia says that she doesn’t mind paying taxes for the subways, because she takes them every day, so she wants to do her part.

Mr. Jones agrees with this, stating that “I will happily pay my fair share [of the transit tax.] I don’t want to, as a new york city taxpayer and resident, avoid paying what is necessary.” He adds, “I think sometimes people expect things like a transportation system to be successful and just work, without their having to contribute anything to it. We the people use it, so we have to pay for it.”

Delays have been racking the subways for a long time. Despite this, when next riding the subways, think about it from someone else’s viewpoint. Try to realize that one delay affects a lot more than you.

After all, as Chris Dooling says, “Listen, I’m stuck here just like you are. If there was anything I could do I would. I can’t grow wings and fly away, we’re all stuck in the same situation. I was a commuter and had to deal with the exact same problem, but now that I know what’s going on, I would never hold a driver responsible for delays.” Neither should commuters.

The decline of the subways have to do with climate change, MTA rules, and bad infrastructure. Though government skirmishes have caused doubt and conflict over funding and jobs, within the next few years, many parts of the subway will become more accessible and easier to ride, thanks to Byford’s plan. These problems impact commuters day to day lives, and though costly, it could save the subways.