“The Lost Daughter”: Tale of the Bad Mother

No Spoilers Below! Letterboxd: isabelwilder

February 15, 2022

The work of Italian novelist Elena Ferrante has always been special to me. I remember my mom reading me sections of her books to put me to sleep as a child, and though I had absolutely no idea what was going on, her words took on this constant and soothing pattern that held such a specific sense of comfort and edge. The year where quarantine pushed everything into limbo, I reached the end of my rope for watching trashy sitcoms and bad Netflix originals. I pulled out “My Brilliant Friend” from the back of the shelf and began reading. Within a month I’d finished the four-part series, devoured the HBO show, and become a devout Ferrante fan.

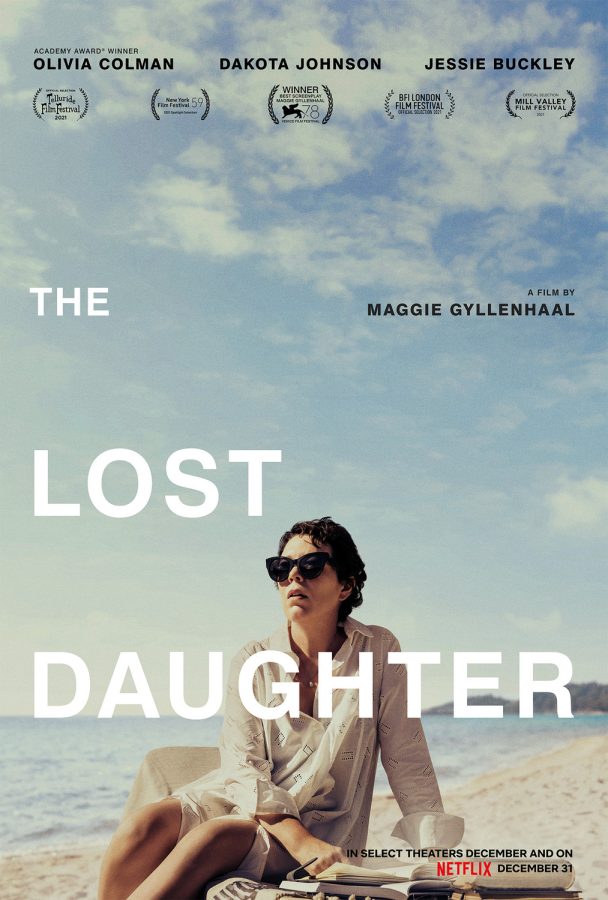

So it’s no surprise that when I heard that Maggie Gyllenhaal was adapting “The Lost Daughter”, my heart sank. I’ve never been a fan of adaptations; I think that they twist and pull from the source material at will, and turn really insightful, nuanced pieces of writing into pandering, Hollywoodized drama (cough cough, “Pride and Prejudice” 2005). I worried that she’d destroy something near and dear to me.

I wasn’t completely wrong- the movie isn’t totally true to the novel, and it definitely doesn’t follow its storyline, but I found myself really enjoying it. The plot is simple: a paranoid, middle-aged woman (Olivia Coleman) vacations in Greece and finds herself drawn to a young mother (Dakota Johnson) struggling to handle this newfound responsibility. Her attachment to this exuberant family brings up long-buried memories about her own children and the space she inhabited with them. The beauty of the movie is the story that’s been erased from mainstream media for too long: that of the “unnatural mother”.

When men leave their children and wives, go off on adventures, or are emotionally removed, they’re seen as aspirational and role models (see James Bond, Indiana Jones, any superhero). Leaving their family at home, sleeping around, finding their path is brave. When women do, however, they’re villainized and called unlikable and unrealistic (like Moiraine Damodred from the Wheel of Time or Shiv Roy from Succession). This can be seen incredibly clearly in novels. When Rivka Galchen wrote “American Innovations,” a work of short stories in which a woman leaves her family for Mexico City and shows little remorse about it, reviews came pouring in, asking if it was “plausible that a mother would feel this way.” The readers didn’t think so: to many, the pinnacle of being a woman is being a mother.

Leda, the older woman in “The Lost Daughter” is determined to reject that type of thinking. Unfortunately, she doesn’t understand how to. Societal grooming and placement into boxes start almost from birth: girls are given dolls and clothes to take care of whereas boys are given trucks and puzzles to mimic professions. This conditioning leads to a common effect with women and children: where personhood and identity are sacrificed for motherhood. Your worth is tied to the success and manners of your child, and your academic inspiration or any other dreams of achievements outside of the family is expected to be shifted aside. Leda notices this, sees it all around her in the attitude of her husband and friends. She refuses to set aside her academia and let her children become her top priority, and through this adamance, alienates them because she was never faced with an alternate solution of balancing responsibility. When the movies dive into her memory it’s revealed that she was a bad parent: someone crude and selfish, who didn’t enjoy spending time with her kids. At one point in her life, she even left them for years- coming back only when she began to miss them. Rather than seeing her kids as parts of herself, she resents them for becoming her life and job to take care of.

This is furthered later in this film when two strange hikers spend a weekend at Leda and her husband’s house. This is presented as an interesting juxtaposition of what her life could’ve been: one filled with freedom, adventure, solitude, and Italian literature (because every movie needs a little bit of pretension.) The hikers ran off together, loved out of wedlock, and left their children, all without any sliver of remorse or regret. Young Leda (Jessie Buckley) looks at them with poorly disguised longing. She yearns for a space to be fully herself, reminding the audience how “children are a crushing responsibility.” Oranges are eaten and handled again and again as signs of innocence and family (vis a vis the lovely and childlike request to peel it all in one piece “like a snake,”) then rotting as her relationship internally and externally with them devolves.

It’s important to also recognize the impact of Leda’s name: stemming from the Greek tale of “Leda and the Swan.” In this, Zeus takes on the form of a swan and rapes a woman named Leda, causing her to birth two of his children from eggs (one of whom later becomes Helen of Troy). Over the years, she has been hailed the “Mother of Mankind”, and the story has come to represent violent eroticism, free will, and motherhood. The brutality of Zeus’s actions and the children that Leda birth come to be more important than her own story. Her own image and personhood are lost throughout the passage of history to represent a larger movement of Sparta and the Trojan War: it becomes merely exposition. I think that this is incredibly important in the context of the movie. The Greek Leda mirrors Coleman’s Leda: both strong women pillaged and laid aside to make way for their children and the stories beyond. Though Leda in the movie has much more strength of will, ultimately they are both two tales of violation and destiny: that the inevitable job of the woman is that of a mother, and the inevitable fate is drifting into memory.

In her novel Outlines, Rachel Cusk speaks about this through one of her cerebral and distant characters, saying that “for many women, having a child is their central experience of creativity, and yet the child will never remain a created object unless the sacrifice of herself is absolute”. This character continues, observing that “one day you realize that all this-the house, the husband, the child- isn’t important after all, in fact, is it the exact opposite: you have become a slave, obliterated! The only hope is to make your child and your husband so important in your own mind that your ego has enough sustenance to stay alive”.

This doesn’t subtract from the fact that for many women, having children is wonderful. They’re amazing mothers who care incredibly deeply about their children while still having an active life outside of their homes. They feel comfortable and satisfied with their life and choices, and find deep gratitude and purpose in helping to raise another human. But regardless of feeling, the act of motherhood beyond the pains of labor is inherently putting another human above yourself. Whether or not you love your child, you become a mother before anything else.

With any other director, this would’ve been shallow and perfunctory. With Maggie Gyllenhaal, it’s gorgeous. It’s labeled as a psychological thriller, but the real terror lies in the movie’s search for acceptance. Leda looks right at the audience and understands how we grow to resent her so quickly for being a poor mother, keeping us complicit in hypocrisy along with the rest of the world. When this complex subject is coupled with incredible acting, beautiful scenery, and a well-written screenplay, “The Lost Daughter”’s Oscar nominations are no surprise, and I’m excited to follow along.