The Wordle acquisition by the NYT & news restriction in the modern era

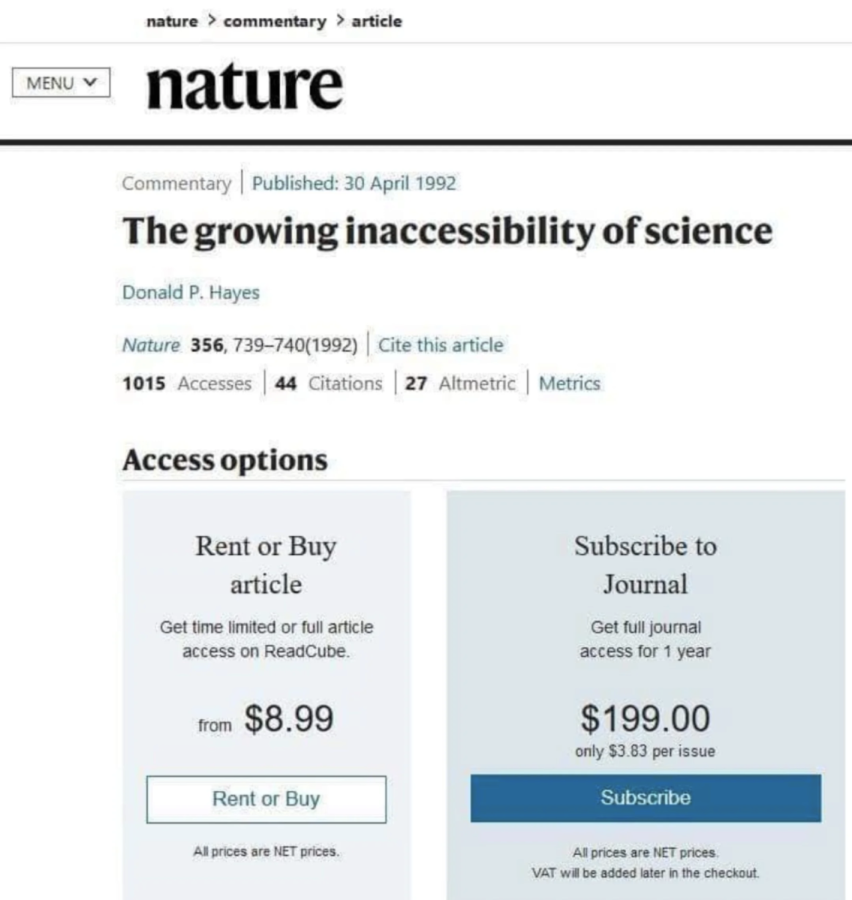

Though nature.com’s twitter— and anyone who has read the article can claim, this isn’t necessarily about paywalls— the term for what is blocking any user from reading this, rather, about “the inaccessible language used in science.” But it became a rallying cry, one of those powerful images that demonstrates just how important it is that knowledge not be blocked and paywalled by a select group of impassioned individuals.

There’s never been a more apt time to discuss media inaccessibility than now.

“The integrity of our democracy relies on the electorate making voting decisions based on facts and truth,” writes Jessie Hsieh of the Kroger Policy Review, and if you don’t have access to these facts and truth, you cannot participate in this democracy in the way that many can, especially if they have the funds to do so.

Financial unreachability in media is such a huge problem— and because “people who pay for news in the U.S. are wealthier and better educated than those who do not,” putting up paywalls can end up creating massive disparities in the news available to different classes.

Because of the propagation of news paywalls in the common media— in publications proven to be reliable and truth-telling, and the massive wealth gaps in the United States and globally, knowledge disparity now will only become greater, as people without the funds for a subscription have taken to news sites without paywalls, which can be much less reliable— and this is only one of many issues the public faces with these paywalls.

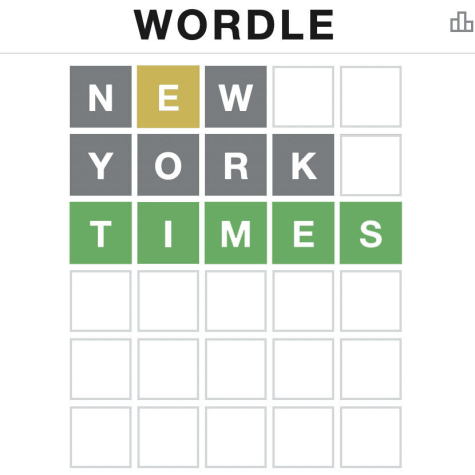

Open-source media and free websites have been taken over & bought over and over again by large companies with these paywalls, with the most recent being January 31st, 2022, when the New York Times bought Wordle, an overnight internet sensation in which one tries to “guess the word” of the day, for a price “in the low seven figures.”

The New York Times has a section on their website dedicated to small games one can play— a mini-crossword, matching tiles, a game called the Spelling Bee. Universally in this sector, they exist under what’s called, by some, a freemium. There are parts of the games that are free, sure, but the real stuff comes with a different subscription than the actual newspaper— you can do the full crossword, you can play as many tiles as you want, you can make as many words in the spelling bee as you want.

With this recent acquisition, the New York Times has said that Wordle will remain “initially” free, meaning that at a certain point, as with their game vertex, this will only be accessible through this other subscription (In actuality, the vertex allows you to do the same three or four puzzles, which is not necessarily a full restriction— but one can see a similar thing happening with wordle), which is something to reiterate: if you read the NYT and enjoy it, and you are a casual fan of a crossword, your only option, at least online, is to do a puzzle that can be finished anywhere from 20 seconds to a few minutes.

Because there’s no half-version of wordle, eventually it will only be accessible through this subscription and will be blocked by a paywall for the rest of us.

Part of the genuine fun of Wordle was that it is free (it is now under an NYT domain, but remains free)— like other feel-good things, it isn’t blocked by anything, it’s just open to everyone for everyone to enjoy.

And that’s being taken away, or, in the words of NYC iSchool sophomore Izzy Apektar, “it was just invented by somebody who wanted to share his game with other people, not only people with a certain amount of money who are able to pay because they can.”

So, why is this important? What does this mean?

It is, put simply, indicative of a larger problem.

Frustration with paywalls is such a common feeling in the digital age. If, say, for instance, you’ve read three articles on Bloomberg.com or the New Yorker, you can’t read the breaking news on that site. It’s extremely frustrating for everyone who wants to keep up with the news but doesn’t want to subscribe to a million sites.

In this year’s first quarter, I was in a class titled Global Current Events, in which it was necessary for me to use the same few articles from the same sources, certainly more than three times. And I’m sure most people who have taken the class can attest to my personal experience. At a certain point, I had to create a Google Doc in which I copy-pasted these entire articles. It was exhausting to even read these articles because of this, and it’s very possible that in another scenario, it could have hindered my progress in the class— had this occurred, I may not have been as successful in the class, due to my lessened resources.

Ari Hope, a freshman at the LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts, has a different solution— saying that they’ve had such an issue with paywalls in research that the solution tends to be “using my mom’s computer,” in Hope’s words.

This isn’t something that one has to tell any reader of this— news paywalls are a vastly complained-about thing—, and it’s easy to think that there’s no point for them, they just exist as a means to restrict the public from news, something that has been historically accessible. There, in the past, there has been a journalistic and widespread idea that news should be as accessible as possible, one shared around the world. In order to be a well-functioning member of society, you must have a well-rounded knowledge of what is happening, both at home and abroad.

But, the sad truth is that the purpose of the society in which we live, and the purpose of any business or for-profit organization, as most mainstream news is, that works in this society, is to make money. Or, from the Kroger Policy Review, “ The unfortunate truth is that most media companies are profit-seeking businesses, so it is not feasible for news outlets to disable their paywalls.”

Or as Apektar says, “Knowing the New York Times…[and] knowing the United States, everyone just wants to make money”, in response to Wordle being put behind a paywall.

So, when newspapers moved online, as paper sales drastically declined, these sites had to create a way to keep up: advertisement or restriction. And there are problems with both. The thoughts against restrictive policies and paywalls of these publications have been stated and stated— it is simply a fact that you should be able to access the news, especially breaking news. It’s something that should be reiterated over and over again: to go to the extreme, if your home is being threatened by a nuclear weapon and you’ve read the 2020 Car Seat Headrest profile on the New York Times a few times in the past few weeks, you won’t be able to know the details. So, a generous solution to this would be to let advertisers onto the website, right? It’s something that a lot do already, so if you get rid of the paywalls and let advertisers in, that’s a solution. Some news sites do it already!

It’s easy to see how that’s wrong— “If you are not paying for it, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold.” in the words of an internet user in 2010 with the username blue-beetle. The freedom of the press is stated in the very first amendment of the US constitution, and the USA prides itself on a free press and freedom of speech. If these publications become wholly supported by advertisers, it’s inevitable that at a certain point, pro-these-corporations ideals will become prevalent — if the vast majority of news sites use it as their sole means of profitability. Journalistic integrity is extremely important, and increased advertising efforts in the press are extremely dangerous.

So what’s our answer? There are a few options that I’d like to present, and to be honest, neither of them are perfect. There are good aspects of these solutions, and, as there always are, aspects that negate them.

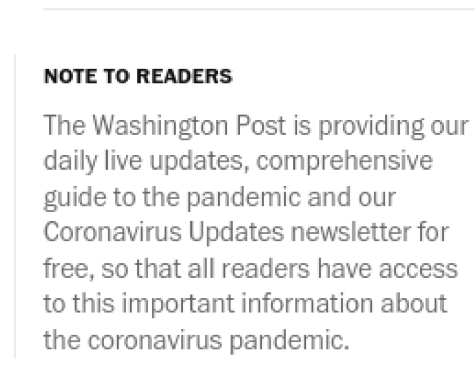

The first being to make it required, by some kind of rule or law, for breaking news to be free. Publications will decide what’s considered breaking news, and it will have to be made accessible. It’s idealism at its best really. But, sadly, due to bureaucracy and the general state of the American governmental system, it will inevitably turn at least somewhat partisan and perhaps won’t pass in any case. However, an example of this in recent memory that’s proven to be extremely beneficial are publications like The Atlantic promising the public that “choosing to make these freely available to all readers, even those who don’t subscribe.” for as long as they are being published.

And the great thing is it’s worked. This idea is one that will work, but enacting it across all publications and with an entire section as long as it exists — which is as long as journalism exists—is a feat.

Secondly, we can take into consideration the BBC. The BBC is made free for British citizens for a simple reason— it’s not free. Citizens pay for it in taxes every year, and because of the expansiveness of the BBC, it is often called the TV Tax. And thus, the website, television, and nearly all of their very large reach in the British world, are made free to all citizens. There’s no reality in which a British citizen could be in the dark about the nukes coming down onto their buildings, unless they are actively avoiding it. But, again, this implementation of a very basic non-partisan, unbiased news source will of course become partisan and of course, have a hard time becoming a reality. Besides, who even knows if it’ll work on such a larger scale.

So, these are two different examples of things that could be implemented to stop the paywall “epidemic” for the most basic of information. And they seem great, and they seem idealistic. It’s a difficult situation, and one that a student reporter can only report on, not provide any concrete solutions— at least not ones that are realistic.

But growing inaccessibility of information is an extremely important issue, and one that needs to be addressed in the mainstream. The New York Times’s acquisition of the site Wordle is just one example of such, and, with the nature of our society, there are many yet to come.