How Tesla went from the verge of bankruptcy to the most valuable automaker in the world

August 29, 2020

The incredible story of a journey from startup to superpower

Tesla has become one of the most engrossing new car companies in decades.

Known for their sleek design and world-class performance, they have entered the mainstream as an exciting new car company. Their self-proclaimed mission is to “accelerate the world’s transition to renewable energy.”

In 2018, Tesla’s popular Model 3 was the best selling luxury car in America, and in 2019 they became the largest electric vehicle company in the world by number of electric cars sold. The company is also the third largest solar panel manufacturer in the United States by Gigawatt hour capacity.

In a 2018 interview for this article at the Tesla dealership in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, Tesla employee Anthony said, “It’s lots of fun to work here. It’s the most fun job I’ve ever had.” (Anthony asked not to have his last name disclosed.) He also said that Tesla had a “very team oriented culture. [Employees] are motivated, but not competitive.”

Many people at the iSchool are fans of Tesla vehicles.

“I think it’s a good company, they make good electric cars. They’re pretty cool cars, but they’re pretty expensive,” junior Adriano Grassi says. “[They have] very good design, very good styling. It kind of seems like eventually what we’ll be driving in 15 years.”

Elias Swift, also a junior, was similarly critical on the price, but still praised the cars themselves.

“The fact that [the $35,000 Model 3] is the cheapest model that they have still makes the overall average [car] pretty expensive.” When asked if he would ever consider buying a Tesla, Swift responded, “I would if I was rich.”

However, he also said he “really liked the design” and that “it’s cool on the outside and on the inside.”

But there’s much more behind Tesla than simply the styling of their cars or the cheapest model they offer. Here is the story behind the world’s most innovative car company.

The Early Years and the Roadster

While Tesla is largely known for its current CEO, Elon Musk, the company was originally conceived by technology entrepreneurs Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning in 2003. Eberhard and Tarpening had previously worked together to found a company called NuvoMedia in 1997, which produced one of the first eReaders, the Rocket eBook.

Using a computer, books could be loaded from the computer onto the Rocket eBook, and those books could then be taken on the go. However, the thing that made the Rocket eBook different was that it could store up to 10 books at once. While modern E-readers can easily store more than 10 books at once, for its time (remember this was 1997) the Rocket eBook was unprecedented. The product was extremely successful, and sold over 20,000 units in 1999 alone despite costing $499. The venture ended up being so successful that the NuvoMedia company was purchased in 2000 for $187 million.

While most people would call it quits there, for Eberhard and Tarpenning this was only the beginning. The two entrepreneurs shared a passion for sports cars and a fear of the future if nonrenewable energy runs out. On July 1, 2003, the two founded Tesla Motors in San Carlos, California. The two had a goal of making electric vehicles (or EVs for short) that were better for both the environment and the consumer. The company is named after inventor Nikola Tesla, who made numerous inventions furthering the use of electricity in modern applications. Eberhard came up with the name while on a date with his girlfriend at Disneyland, who would later become his wife.

The plan for the company was to modify an existing car, the Lotus Elise, to become electric by removing the engine and installing a new battery. They would also put in some existing electric car technologies from a separate company named AC Propulsion. AC Propulsion had a handmade electric car called the Tzero that Eberhard had stumbled across in his initial research. The Tzero was odd and quirky, but extremely quick and fun to drive. It proved electric cars could be fast and enjoyable in a way nothing else did, and was one of the main ways Eberhard convinced people to join his company. The plan for Tesla was to license the electric powertrain (the parts of the car involved with generating power and transferring them to the wheels) from AC Propulsion for the modified Elise chassis. Most of the chassis would be manufactured by Lotus, while Tesla would manufacture the battery and drivetrain and put it all together. With a car to base itself off of, technology to work with, and a manufacturing partner, they would iron out the kinks and sell it to the public.

Eberhard was the company’s CEO from its inception in 2003 until August 2007. While Eberhard and Tarpenning were able to finance the company for about a year, they soon needed more funding, as creating and running a car company requires an immense amount of money. One of its first investors was Elon Musk, a cofounder of PayPal. Musk gave $7.5 million in the company’s first funding round, more than anyone else in the round. Musk then became chairman of Tesla’s board, and was heavily involved in designing their first car.

By 2006, Musk put out a blog post titled “The Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan (just between you and me)” outlining his vision for the company. While the post was largely ignored at the time, it would go on to change the face of the automotive industry forever. Musk’s “Secret Master Plan” consisted of making the Tesla Roadster first as a low volume, high-price product to break into the auto industry, get experience in making vehicles, and prove the viability of EV technology. Using that money Tesla would make a new and more affordable sporty 4-door family sedan, and would then use that money to make an even more affordable third car. Musk also stated interest in providing solar panels through a joint venture with SolarCity, a company of which Musk was also the largest financial backer.

However, before any of that would happen, a changing of the guard at the company needed to take place.

In August 2007, Eberhard was ousted as CEO of Tesla, and instead moved to president of technology. Tesla’s board of directors had a meeting without him, and decided that he was to be removed from the job.

“There was no discussion,” Eberhard would say of the event. “I didn’t get to hear what they said. I didn’t get to defend myself. I felt totally stranded… “I never figured out what was said about me to those people.”

As president of technology, Eberhard did not have a say in the direction of the company. While Eberhard stayed at Tesla for a bit, he soon left the corporation after being unhappy with his now minimal role.

After Eberhard left, a search for a new CEO would commence. Michael Marks, the former CEO of electronics manufacturer Flextronics, would take the role temporarily after Eberhard’s firing, but he was always meant as an interim leader while the company found someone better. On November 27, 2007, the company would eventually bring in Ze’ev Drori, the former CEO of car alarm manufacturer Clifford Electronics.

Both Marks and Drori worked to sort out production and management issues to allow Tesla to put out their first ever car, the Tesla Roadster.

A little over 2 months after Drori began his tenure, Tesla would finally get the car out to market. The company gave their first production roadster to Musk on February 1, 2008.

The car started at $98,950 and had about 220 miles of range. It was the first production electric car in history that could travel over 200 miles on a single charge, and was also the first production electric car to use lithium-ion batteries. In 2013, lithium-ion was the most common form of battery in use, and it is still the standard battery of portable smart devices such as laptops and phones. Tesla’s decision to use lithium-ion batteries stuck around – lithium-ion is currently the most common form of battery for both fully electric and plug-in hybrid automobiles.

While the Roadster was intended to be a modified Lotus Elise, calling the final product a “modified” Elise would be a stretch. One example of this was given by Darryl Siry, a Vice President at Tesla, who released a blog post after the first Roadster delivery that described just how different the Elise and the Roadster were. Siry said that the two only shared 7% of the same parts, and that “if you… started throwing away parts that aren’t carried over… you would basically be left with a windshield, [a] dashboard [with airbags], front wishbones and a removable soft top.”

This was part of the reason the first car wasn’t made until almost four years after the company was founded. While taking out the engine and installing an electric battery, powertrain, motor and other components seemed relatively simple at first, it turned out to be unimaginably complex and difficult. In what would become a recurring theme for Tesla, an underestimation of manufacturing difficulties caused significant delays and defects.

In a later interview, reflecting back on the Roadster, Musk described the plan for the initial Roadster as a “super dumb strategy” that was “based on two false premises.” First, the original team assumed that “[they] would be able to cheaply convert a Lotus Elise and use [it] as a car platform.” However, putting an electric battery in and reworking the car was far more difficult than anyone would’ve hoped. The added weight and complexity meant they had to redesign more and more of the car, until they were left with 7% commonality across all parts.

The other major assumption was that they had assumed they would be able to take powertrain technology from AC Propulsion and use it for the Roadster. Musk said that “the AC Propulsion technology did not work in production,” and that “they ended up using none of it in the long term” having to “redesign everything.” Given how fundamental a powertrain is to a vehicle, it ended up heavily compounding the complexity of the resdesigns.

However, the team also had another item that worked against them – perfectionism. The team was highly dedicated to making the car as nice as it should be, so much so that they kept improving little things about the car that weren’t fully necessary. Eberhard later described it like this:

“Each of these is a reasonable decision… [but] you have to consider that it’s going to cost more money and cost on the schedule, and that was never accounted for… We had to figure out how to supply hundreds of components for a company in England by a team in Silicon Valley that had never done that before… That was the hardest thing that I didn’t expect.”

With all the issues that plagued the car, Tesla didn’t announce the start of “general production” until 2010.

While the car was generally well received, it didn’t change the fact that the company had never made a profit. By late 2008, things started to get desperate. The Great Recession was in full effect, devastating the economy. Car brands in particular were hit very hard – General Motors and Chrysler filed for bankruptcy the next year. Investments were hard to come by for any business, much less for an electric car startup that had never made money. This was all exasperated by the fact that Tesla was beginning to run short on funds. As time went on, the situation continued to get worse for them until it eventually looked like all was lost.

As 2008 went on, all three of the big automakers in Detroit famously got “bailout” packages from the government. Tesla, on the other hand, was still desperate for money to keep the company afloat. By Christmas Eve 2008, after the Big Three automakers had already been approved for funding from the government, nearly everyone thought Tesla was done. Leadership and production were a mess. The company was on their third CEO in two years (not including the interim CEO) with Musk having taken the role over from Drori in October of that year. By this point he had put in over $55 million of his own money into the company, and just didn’t have more to give. No one else seemed willing to invest with how tight money was at that point. Marc Tarpenning and Martin Eberhard, the original two entrepreneurs who funded the company for its first year, were gone. While the company seemed like it was destined to fail, a Christmas miracle ended up giving Tesla just enough to get through the year. That night, the company was saved from becoming history by Daimler AG, the parent company of Mercedes Benz.

On December 24, 2008, Tesla closed a funding round at “the last hour of the last day that it was possible,” per Musk. With this investment, Daimler invested $50 million into the company, saving it from otherwise certain death. In a later interview, Musk said that “[Tesla] would’ve gone bankrupt a few days after Christmas if that round hadn’t closed.”

With this lifeline, Tesla was able to step back from the edge of insolvency and continue its operations. But even despite almost folding, the company still had grand ambitions, and appeared keen on executing them.

One of their foremost concerns seems to have been the next step in the “secret plan” – creating the more affordable, higher volume 4-door sedan. In August of 2008, Tesla had hired Franz von Holzhausen to help make this happen. Holzhausen was a former designer for Mazda and General Motors, who would go on to strongly influence Tesla. Since joining, he has designed every vehicle in the company’s history with the exception of the original Roadster. But one of his biggest successes would turn out to be his first attempt.

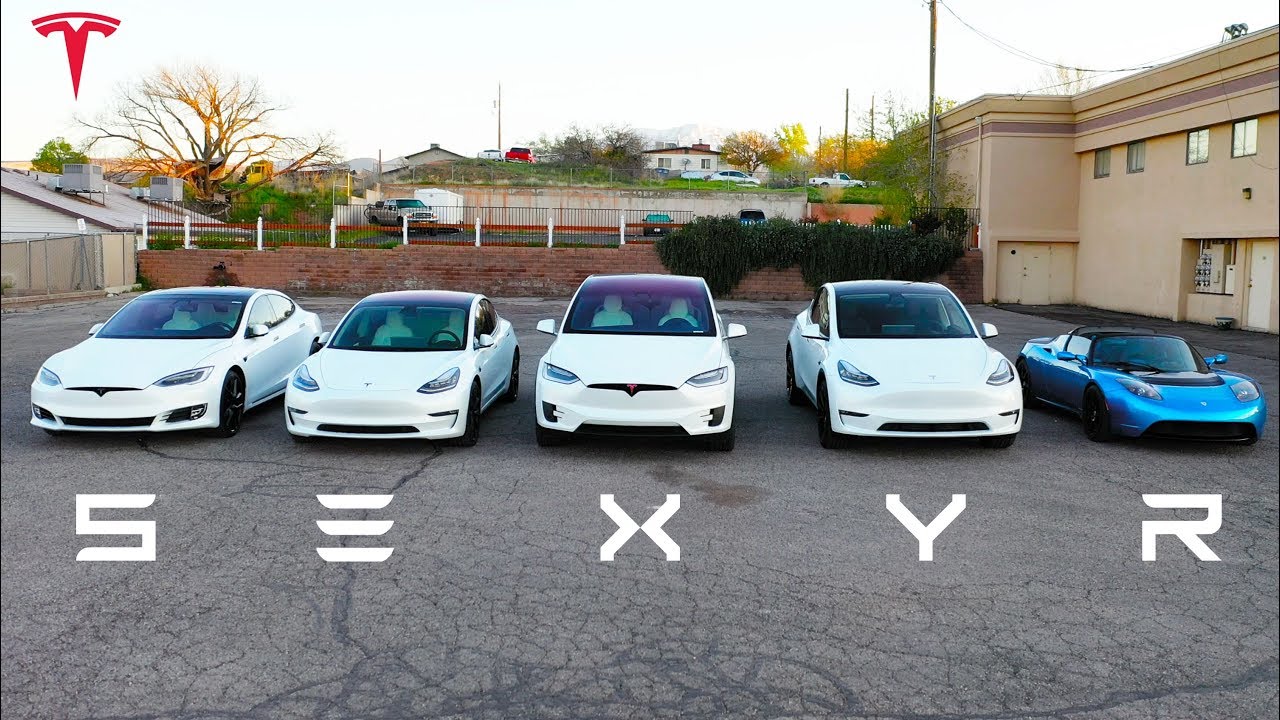

On March 26, 2009, the long-awaited four door car alluded to in Musk’s original master plan was unveiled as the “Model S.” Keeping with the trend set by the Roadster, the car was named based on its classification, with the S being short for sedan per Musk. First deliveries of the car were expected in the final quarter of 2011. However, while the car was now shown to the public, the company was still far from ready for their first crack at mass production. In order to get to that point, Tesla would need to raise money like it had never done before.

And in the first half of 2010, that’s exactly what it did.

First, in January of that year, Tesla received a $465 million loan from the U.S. Department of Energy. The investment was the largest cash injection in the company’s history, more than doubling the total amount of money raised up to that point. It’s worth pointing out that this loan was wholly separate from the “bailout” ones offered to the big automakers in Detroit, as it was part of a program for developing energy efficient vehicles instead of supporting companies for the sake of the economy.

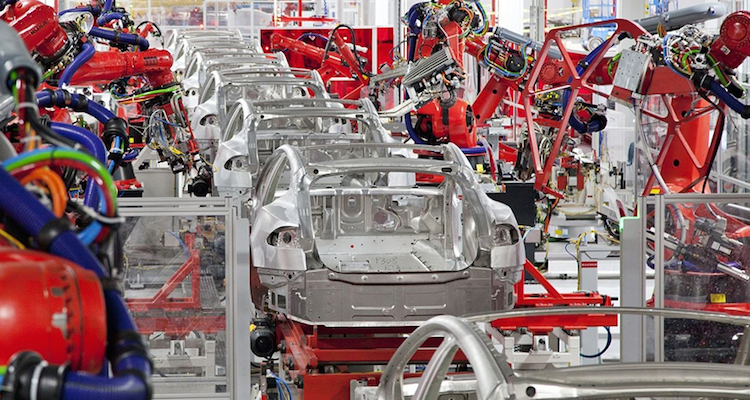

Tesla planned to use $365 million for an assembly plant for the Model S and $100 million for an electric powertrain manufacturing plant. At that time, the company was developing powertrains for other companies’ electric vehicles, which they eventually did for automakers such as Smart USA and Toyota. After receiving their loan, the company bought a plant in Fremont, California, for $42 million. The factory was previously owned by NUMMI, a joint venture between General Motors and Toyota that had been shuttered. In April 2018, The Tesla Factory (as it is now called) was ranked by Cnet as the fourth largest building in the world by footprint, one ranking ahead even of Boeing’s Everett factory for airplane manufacturing.

While Tesla announced that they would be building a Powertrain manufacturing site in 2010, the building they had announced for their site (3500 Deer Creek Road) is currently listed on their website as their headquarters with no mention of any manufacturing. They have not announced a separate powertrain manufacturing facility.

By this point, many people and companies were interested in investing in the company. To accommodate this, Tesla had begun preparing for their initial public offering. In an initial public offering, or IPO, a company sells shares of equity to the public for the first time. This is seen as a sort of business right of passage by many, and if successful can prove that Wall Street has confidence in the company. However, the more important and obvious reason to do it is that if investors buy the shares – and especially if the shares increase in value as the day goes on – it can raise a lot of money for businesses that need it.

In January 2010, the company filed a prospectus with the Securities and Exchange Commission for its IPO, and by June it went public on the Nasdaq stock exchange. It was the first American car company to go public since Ford did in 1956, a 54-year gap. Per Investopedia, “it offered 13.3 million shares at a price of $17 per share, raising a total of $226.1 million. On the day of its IPO, shares of Tesla Motors increased by 40.53% and closed at $23.89.” By the end of its first trading day, the company was valued at a cool $2.2 billion – pretty impressive for a 7-year old car company that only sold one vehicle model. All in all, the IPO was highly successful in both legitimizing Tesla as a car company and raising a lot of money.

With a new, higher volume and more forward-looking car on the horizon, Tesla pulled the plug on the Roadster in January 2012. In its lifetime, only about 2,500 Roadsters were ever sold. To date, it is the only car Tesla has ever discontinued.

Once it had the design, funds and production facility in place, Tesla made the Model S happen. The event for the Model S’ first deliveries was on June 22, 2012, at least five months after the originally planned first deliveries and five months after the end of the Roadster.

The Model S

Unlike the Roadster, the Model S was designed from the ground up as a fully electric vehicle. Tesla was not the first company to mass-produce an EV that was not based on a pre-existing model, as other cars like the Nissan Leaf and GM EV-1 had come before. What it did make, however, was an electric car that was luxurious, shattered EV stereotypes, and set the stage for a new generation of automobile.

Up to that point, there really had not been a long-range, practical EV for sale. Mass market offerings from automakers had been released, but no one else would sell a car with 200 miles of range for another four years. Tesla’s Roadster did have a long 220 mile range, but it cost over $98,000. It being a sports car also did little to shake the perception that practical EVs for the masses were years away, if they would ever come at all. What made the Model S so influential was that it shattered all the previous perceptions about what an electric car was or what it could do, and pushed the industry forward in the process.

For one, it was largely agreed to be stylish. Consumer Reports described the car as having an “innovative design,” while MotorTrend called it a “beautiful breadwinner.” Describing the exterior, Edmunds stated that “the sleek body is a pleasure to look at.” This is especially important given what EVs had looked like in the past: Edmunds summed it up well describing previous EVs styling as akin to “podlike transport,” unlike the Model S’ “stunning good looks.” While looks are highly subjective, many of the industry’s leading reviewers seemed to praise the car’s exterior, indicating a general sentiment of fondness.

While the Model S was noted for its sleek design, that didn’t mean sacrificing usability. As MotorTrend pointed out, the initial Model S “can carry almost as much stuff [cargo space] as a Chevy Equinox [an SUV], and is more efficient than a Toyota Prius.” The EPA gave it an 88 miles per gallon equivalent (MPGe) fuel economy, and a 265 mile range. The EPA also said that a given owner would save $2,000 in fuel costs over 5 years compared to an average new vehicle. Just like the original Roadster, the EPA range on the S was better than any other electric car in history at that time.

Impressively, while the Model S was highly practical, it also managed to be extremely fun to drive. When it first came out, the performance variant could do zero to 60 in 4.3 seconds, beating the BMW M5 in a drag race done by Automobile Magazine. MotorTrend described the ride quality as “impressive,” while Edmunds called it “smooth and agreeable.” Road & Track praised “tight” steering in their initial test drive, and noted how the Model S “still rides smoothly” over bad roads. Automobile Magazine asserted that “the Model S exhibits impressive body control and vacuumlike grip” when cornering.

The Model S’ performance was impressive at launch, but new versions have gone from eyebrow-raising to record breaking. While a 0-60 above 4 seconds was once the highest trim performance variant, the current slowest option does it in 3.7 seconds and the fastest does it in just 2.3 seconds. As of February 2020, MotorTrend has the highest performance variant of the Model S as the quickest production car they’ve ever tested.

While the Model S had (and still has) a lot going for it, the most important thing about it is how it pushed the industry forward. The Model S had many innovations that the auto industry had never seen before, and some of which it is still catching up with.

First, there’s the interior. The Model S had a minimalist interior that was vastly different from any other car on the market. The Model S’ controls were centered not around physical buttons, knobs and dials, but instead a massive 17 inch touchscreen display – the largest of any passenger car at the time. As of late 2019, the Model S was tied with another Tesla vehicle for that record. The Model S’ use of a large touchscreen and lack of physical controls has been translated onto every other Tesla to come out since, and many know it is a signature design aspect of the company.

While the skeuomorphic touch screen icons were in line with the software design of the time, today they have largely fallen out of fashion. Luckily for Model S owners, the car was the first in history to utilize what would go on to become another standard Tesla selling point: over-the-air software and firmware updates. Just a few months after the first deliveries of the vehicle, the Model S became the first car in history to receive a firmware update. This update could be done over either Wi-Fi or over the car’s built in 3G cellular connection. If you’ve ever updated an application or operating system on a smart device such as a tablet or computer, Tesla’s cars do the same thing – they download data that can better change the software for the user.

With how much the car relies on its center screen, the fact that they can update that screen for better functionality and to add new features makes the cars age much better. For example, one of the biggest complaints with electric cars has always been the charge time: while gas cars can drive into and out of a station filled up in less than five minutes, electric cars have always been slower to charge. In order to address this, Tesla has put a number of entertainment options into their cars. Today, the cars boast video games, a music making program, karaoke (aptly named “caraoke”), YouTube, Netflix, Twitch, and more to keep buyers engaged. And these updates come frequently: popular tech YouTuber Marques Brownlee has said that since getting a new Model S, the car got more software updates than his smartphone did.

In addition to new features, updates can actually increase performance. While some software updates bring minor improvements, others have shaved a tenth of a second off the 0-60 time or even increased the car’s range by 17 miles in one case.

The 2012 Model S was a really good car. So good, in fact, that it won an almost dizzying amount of prestigious awards. Consumer Reports gave the car a 99/100 overall rating, tied for best in Consumer Reports’ history at the time. Edmunds proclaimed that “not only is the 2012 Tesla Model S the best electric car you can buy today, it’s also one of the best luxury sedans available.” Automobile Magazine gave the car their 2013 Automobile of the Year award, despite it going against “the strongest [competition for the award] in recent memory.” TIME Magazine named it one of their 26 best inventions of 2012, alongside such items as the Curiosity Rover and the Deepsea Challenger Submarine that went to the bottom of the ocean. In a later TIME list of the best gadgets of the 2010s, the 2012 Model S also notched a spot. In its entry on that list, TIME said that “the [Model S] has slowly reshaped the trajectory of the automotive industry,” and the car felt “like a vehicle from 2022 instead of 2012.”

MotorTrend’s 11 judges unanimously named The Model S their 2013 Car of the Year. The S was the first electric car to win the award in what was at the time a 64-year history. In a similar fashion to Automobile Magazine, MotorTrend gave the award to Tesla despite it facing “a number of very, very strong contenders from… historic, very large brands” that had “no slouches.” This was also the “first time that anybody on [their] staff could remember it being unanimous.” At an event for the award, Musk described winning the accolade as an “important day” in which “the gears of history moved.” In 2019, in honor of the 70th anniversary of MotorTrend’s Car of the Year Award, MotorTrend named an Ultimate Car of the Year that represented the best out of any car they had reviewed – and it was none other than the original Model S. In their announcement, they stated that “no vehicle… can equal the impact, performance, and engineering excellence that is our Ultimate Car of the Year winner, the 2013 Tesla Model S.” Business Insider called the Ultimate Car of the Year award “one of the most prestigious honors in the automotive industry.”

The Model S was the first mainstream car to prove that EVs can be cool, practical, and enjoyable all at the same time. There are very few – if any – cars that have changed the future of the automotive industry the way the Model S did. MotorTrend stated its impact well in saying that “the Model S changed the way the world thinks not only about electric cars but also about cars in general.” Every other electric car that would follow the Model S was heavily influenced by it, as it showcased the true unrealized demand for an EV with no compromises.

This much was reflected in the sales figures. In the fourth quarter of 2012, the Model S was the fourth bestselling plug-in vehicle in the world, and the second best selling all-electric vehicle behind only the Nissan Leaf. This was despite the fact that the S cost a base $57,400 when it first came out. The performance model went up to $87,400, and the limited production Signature Edition went up to $105,400. However, there was also a $7,500 tax credit on all purchases, which brought the effective minimum price tag to $49,990 before variable gas or maintenance savings. For reference, Edmunds estimates the average new car purchase in December 2012 was about $32,296. In other words, the Model S had a premium sedan price tag – but people were buying en masse despite this.

By 2015, the Model S was the best selling all-electric vehicle in the world. In 2016 and 2017 it was the bestselling plug-in vehicle in the world, meaning it also beat out cheaper plug-in hybrids. This was despite the fact that the Model S’ effective base price actually increased over time – from $49,900 at launch 2012 to $62,000 in late 2017. At the time of this writing, the car starts at $74,990.

The increase in price is largely a result of the company phasing out lower end battery packs. For example, the aforementioned sub-$50,000 launch base model had a battery that could go 160 miles, while the $62,000 model had a battery with 259 miles of range.

Expansion beyond Automobiles

The Model S is now one of Tesla’s most instantly recognizable products, but another one of Tesla’s most important selling points was introduced just a few months after the Model S: the Supercharger. A supercharger is Tesla’s equivalent of a gas station, where you can pull in, recharge your car, and then continue driving as fast as possible. In September of that year, they unveiled their first six supercharging stations, which they had constructed in secret. At the time of this writing Tesla has just under 2,000 supercharging stations, with over 17,400 individual Superchargers. Today, the Supercharger network extends worldwide to places such as Hawaii, Mexico, Canada, most countries in Europe, various places in Asia (particularly China, Japan and South Korea) and the Middle East. It also covers every state in the contiguous United States.

2012 was a big year for Tesla, but 2013 would also be important.

In Q1 (quarter 1) of 2013, Tesla achieved a big landmark when it recorded its first quarterly profit as a public company, making $11 million. However, the profit was very meager, as it was only about an eighth of the amount of money they had lost the previous quarter. Their newfound profitability wouldn’t last long, as their next quarterly profit wouldn’t come for another three and a half years until Q3 2016. At the time of this writing, Tesla has never posted an annual profit.

None of this would have been possible without Tesla’s sizable loan from the Department of Energy. As a sign of appreciation, and with the company in good shape after its first profit, Tesla

repaid the entirety of the loan, with interest, nine years ahead of schedule. It was the first automaker to repay the U.S. government without also costing taxpayers. This is because while Chrysler technically repaid the government first, the U.S. Treasury sold equity it had in the company back to Chysler at a loss of $1.3 billion.

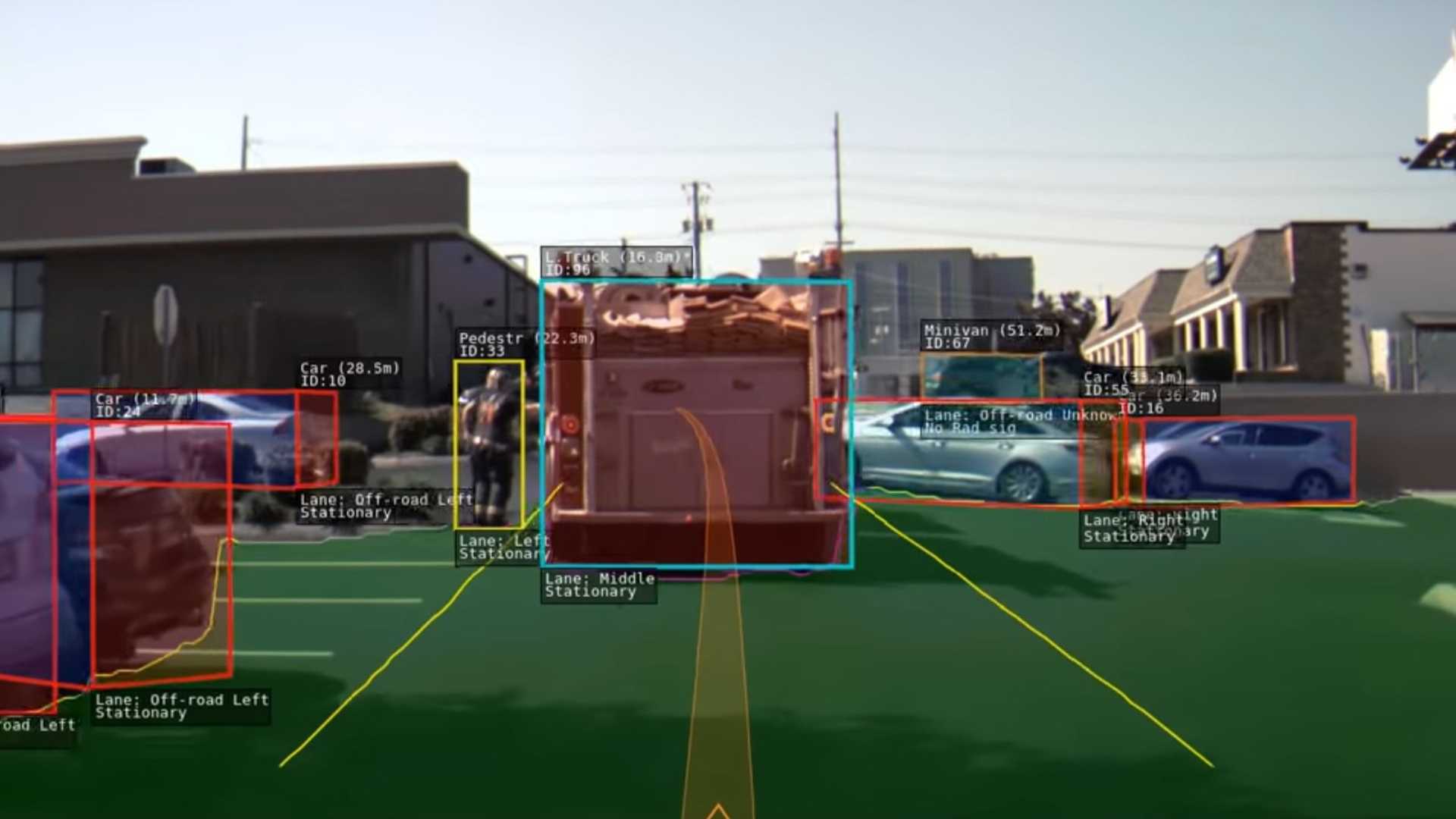

Also in 2013, Musk first started talking about the idea of making the cars self driving – or as he called it, adding an “autopilot” feature.” He stated he had been talking to Google about using some of their self driving technology in Tesla cars, although from the outset it seemed he was sure they would be developing at least some proprietary technology. Musk was unhappy that Google was largely basing its system on a technology known as LIDAR.

LIDAR, short for Light Detection and Ranging, utilizes a system that shoots out laser light pulses in order to determine the size, speed, and direction of the objects around it by measuring the reflections with a sensor. By keeping track of how long the beams take to reflect, the LIDAR system can calculate the distance of objects around it in a way not dissimilar to echolocation. Self driving cars use a LIDAR system that shoots out continually spinning 360 degree lasers in order to determine objects in every direction of the car, at a rate of millions of times per second. Tesla, however, has consistently eschewed using LIDAR in its car systems, instead preferring to rely wholly on sensors and cameras for its systems. For example, years later at an autonomous driving conference, Musk said that “LIDAR is a fool’s errand. Anyone relying on LIDAR is doomed.” This was a bold statement – as Forbes’ Lance Eliot put it, “nearly all of the autonomous car makers are making use of LIDAR, other than Tesla.“

A little over a year after repaying the government loans, Tesla was feeling generous. So on June 12, 2014, they announced that all of their various patents – existing and in the future – would be available for anyone to use free of any lawsuits. In addition to this, Tesla states that this is a legally irrevocable pledge. Specifically, the pledge states that Tesla cannot initiate a lawsuit for companies using their patents so long as it is done in “good faith,” the meaning of which is explained in-depth on the Tesla website’s legal page.

Throughout all this, Tesla was still growing its core business as a car manufacturer and working to ramp up production. In order to exponentially increase the number of cars made each year, there was one specific part of the manufacturing process that necessitated an overhaul: getting the batteries. Batteries determine how long an EV can drive, and for lithium-ion batteries in particular, if implemented incorrectly can catch on fire (think the Samsung Galaxy Note 7). At the moment, batteries are also the single most expensive part of an electric vehicle to manufacture. Knowing this, Tesla set out to develop a factory the likes of which had never been seen before, which was aptly named the Gigafactory. The Gigafactory, which ended up being located near Reno, Nevada, is a joint venture with consumer electronics and battery giant Panasonic. It’s one of Tesla’s most ambitious projects to date, and has no shortage of aspirations.

The Gigafactory was designed with the intent of being the largest building in the world by footprint when completed, and the second largest by volume. It was also planned to be powered by 100% renewable energy through a combination of solar, wind, and geothermal power. The solar power would be generated through the largest rooftop solar array of anywhere in the world. All this renewable energy would allow the factory to have net-zero carbon emissions, an impressive feat given the demands of running a facility that size. All of this would be done through a factory that would be heavily automated, but still employ 6,500 people in full production. Musk also said that Tesla would “build recycling capability right into the factory.”

Tesla’s expectation was that by 2020, the plant alone would make as many lithium ion battery cells as the entire world did in 2013. Through the Gigafactory, Tesla would be able to hit a new goal: produce 500,000 cars per year by 2020, a more than 22 fold increase over the number of cars it sold in 2013. The 500,000 car per year goal would go on to become a benchmark and an aspiration for the company to achieve, as making that many cars per year would signal the beginning of true mass production. Once they achieved that scale, consistent and high profitability was feasible. This would be a big benefit for Nevada, as it would bring a projected $100 billion boost to the Nevada economy over the course of two decades. It was important for Nevada that this be true. When deciding upon a location, Tesla pit states against each other to see who could offer them the most incentivizing deal for location, and Nevada won with up to $1.3 billion in tax breaks over 20 years if certain thresholds were met.

Excavation work on the site began in July 2014.

In addition to expanding their production capabilities, Tesla was also working to expand its automotive business in terms of the models it offered. The Model S did a great job of addressing the premium sedan market, but there were also other parts of the car market that merited a car from Tesla. One of the most glaring of these was the SUV market, as by July 2014 the vehicle type was the most popular style of car in the United States. In order to address this, Tesla decided to make their own luxury SUV, which they called the Model X.

Model X and the Beginning of Tesla Energy

The Model X, Tesla’s third production vehicle, had its first deliveries in September 2015. This was a noticeable misstep for the company, as the first deliveries occurred just under two years later than expected. The X, which had been unveiled in 2012 a few months before the S’ launch, was a slight deviation from the original Tesla master plan. The original plan was to start with the high end Roadster, use that to fund the lower price and higher volume Model S, and use those funds to make an even lower price and higher volume third car. Instead, they decided to have the Model X serve as a stop gap between the S and the originally planned third car – or as Musk went on to call it, “step 2.5.”

Tesla’s initial plan was for the X to essentially be a Model S that was modified to be a little more SUV-like, as this would make it easy to produce. But when it launched, the S and the X shared about 30% of the same parts, half of the 60% goal the Tesla team had when first designing the vehicle. The reason for this discrepancy is similar to one of the main problems with the production Roadster – they could keep making it better in incremental ways, so they did, until the car was a headache to manufacture and had all sorts of complications. Years later on a call with investors, Musk said the following:

“The mistake we made with the Model X, which I really think we have taken to heart at Tesla, is that we put too many new features and technologies, too many great things all at once into a product. In retrospect, it would have been a better decision to do fewer things with the first version of the Model X and then roll in capabilities… I do think there is some hubris there with the X… The net result, however, is the Model X is an amazing car. I honestly think it is the best car ever. I’m not sure anyone is going to make a car like this again. I’m not sure Tesla would make a car like this again.”

The car went on to face multiple recalls and a number of issues, such as the center touchscreen leaking a gooey liquid, the power steering not working and the second row seats not locking into place.

While the X may have had some problems, Musk was right about it having a lot of features. One of the most noticeable and distinct features of the Model X is its doors. The front doors are fairly commonplace, aside from the unique Tesla door handle design where the handles are kept inside the body until it detects a key (which can be your phone) nearby and they jut out. But the rear doors are much more grandiose. The Model X has what many have called falcon wing or gull wing doors, meaning that the hinge for the doors is not on the side of the car, but instead on the roof. This causes the doors to open upward, instead of out to the side, similar to the famous DMC DeLorean.

While this door design is rare even for exotic or conceptual cars, it was (and still is) unheard of for a practical, family-oriented SUV that actually went into production.

For practicality, the Model X has an optional third row that allows it to technically seat seven people. With this being said, comfortably seating one or more full sized adult(s) in the rear row is a stretch, especially for extended periods of time. In addition to an extra row, it also had much more cargo space compared to the Model S – a total maximum of 88.1 cubic feet, 47% more than the S’ 60 foot maximum.

However, something the two cars share is performance way ahead of their class. The lowest range Model X sold to date had 200 miles of EPA range, while the two trims of the car currently offered have either 305 miles or 351 miles. The 351 mile variant is currently the second longest range EV available for purchase, behind only the longest range Model S.

With the performance and Ludicrous+ upgrades, the 2020 Model X can do 0-60 miles per hour in as little as 2.6 seconds. This makes it tied for the fourth quickest production vehicle in the world – faster even than a 2006 Bugatti Veyron or a 2017 Lamborghini Aventador S. When compared to other cars in its class, the Model X stands out even more, boasting the fastest 0-60 time of any SUV in the world.

But that speed doesn’t mean sacrificing safety. The Model X was the first ever SUV to earn 5 stars in every crash test from independent NHTSA testing, giving it a perfect 5 star safety rating. This also earned it the lowest probability of injury of any SUV tested by the organization. The NHTSA, short for National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, is a U.S. government agency that tests motor vehicles. When it earned this accolade, the only car with a lower probability of injury was the Model S.

While not quite as important for most people as the safety, another interesting characteristic of the car is its towing ability. The car’s powerful and instantaneous torque allows it to tow heavy weights, with it being rated to tow up to 5,000 pounds. In May 2018, the X showcased this ability when it broke the Guinness World Record for the heaviest weight towed by an electric vehicle, towing a 5,500 pound Boeing 787-9 airplane.

Overall reception to the Model X was mixed. While some liked the car and its brazen features, others found them to be tacky and unnecessary. For example, in their initial reviews, MotorTrend called the Model X a “high-quality luxury SUV” despite its flaws, and WIRED described it as “a vehicle that somehow makes an SUV not just cool, but desirable.” Consumer Reports, on the other hand, exemplified the more dissatisfied crowd of reviewers, calling it “more showy than practical.”

While it may not have been nearly as high-profile as the Model X, Tesla also launched a new line of products in 2015 that signaled their approaching the end of the master plan: Tesla Energy. When it was first unveiled, Tesla Energy consisted of two products, called the Powerwall and the Powerpack. The Powerwall was a sleek home battery, where a homeowner could take energy created through solar panels and store it for later in the Powerwall. The Powerpack was also a battery, but was aimed at business and utility companies instead of individual homeowners. While the Powerwall was designed for a single home and could be attached to a wall, the Powerpack was much larger, and designed to store massive amounts of energy, likely for thousands of homes or industrial buildings.

The introduction of Tesla Energy signaled a fundamental shift in the company’s future: not only would Tesla build electric cars, but they would also build comprehensive and cohesive energy ecosystems in which the cars would play a central role. In order for the company to work on solar panel energy generation like Musk had outlined in his original document, customers would first have to be able to store that energy somewhere, which is exactly what Tesla Energy offered.

But while the future may have been a complete ecosystem, that didn’t change the fact that Tesla was at that time still very much an electric car company, and still had an ultimate goal of mass producing an affordable EV. Now, Tesla had the funds and the scale to finally make it happen.

Their next car would be the most important in the history of the company. The Roadster had first proved that production EVs could be long-range, cool, and fun to drive. The Model S proved they could be practical and premium, and the X allowed for more versatility and showcased engineering prowess. But the company had yet to prove it could make an electric car that was truly affordable, and that the average person could feasibly buy. This is to say, they had yet to achieve the pinnacle of their master plan. And this is what they would unveil next.

By this point, the company had already stated the name of the car, some of the specs, and the intended price point. But it was on April 1, 2016 – 11 years and eight months after Elon Musk penned the original Tesla Master plan – that he unveiled the affordable car that Tesla had been striving for, named the Model 3.

Model 3 Unveiling and Completion of the Master Plan

According to Musk, the car was originally intended to be called the Model E. For how much work had to be done for the car to even exist, Musk’s reasoning for the naming convention of the car was initially based on a surprisingly juvenile joke:

“We [had] the S and the X, and a friend asked me at a party ‘hey, what’re you going to call your third generation car?’ I said, well we have the S and the X, we might as well make it the ‘E,’ you know? And then it kind of stuck, even though I was just kidding. And then just to sort of add to it, we also just trademarked ‘Model Y.’”

The only problem was, Ford had the trademark for the Model E name and threatened to sue Tesla should they use it. Ford never built a vehicle with the Model E name, but didn’t want someone else to out of concern that it sounded too much like their famed Model T.

In 2014, a Ford spokesperson told CNN Money that “Ford and Tesla entered into a contract in 2010 in which, among other things, Tesla agreed not to register or use Model E. When Tesla later sought to register the Model E trademark, Ford insisted that Tesla abide by the parties’ earlier agreement.” Tesla’s way of getting around this predicament was to call the car the Model 3, as the letter 3 is similar in shape to a backwards “E.”

The Model 3 is a sedan like the S, but it’s smaller, slower, a bit less heavy, and has less range. The 3 was built on Tesla’s third generation vehicle platform, with the Roadster platform being the first and the S and X platform being the second.

One of the biggest differences between the Model 3 and the Model S or X is the interior. While the S and X both use a vertical 17-inch touchscreen, the 3 instead opted for a horizontal 15-inch touchscreen. Also unlike the S and X (and every other car on the market) the Model 3 has no speedometer behind the steering wheel. Instead, drivers have to glance over to the top left of the touchscreen in order to see how fast they’re going.

Franz von Holzhausen said in an interview with Automobile Magazine that “from initial sketches to production launch was about two years.”

When the car was unveiled, Musk announced it would start at $35,000 with a base range of 215 miles. That price may seem like a lot to some, but it was actually fairly typical for most – per Kelley Blue Book, the average new car cost about $34,000 in 2016. This figure would also take them right into the price range of luxury automakers such as Audi and Mercedes-Benz, who today have cars that start at $33,300 and $33,495, respectively.

Aside from the car itself, the Model 3 event also inadvertently showcased another asset from Tesla – the alluring power of their brand. Before the presentation started, the car was only available for pre-order from Tesla’s retail stores, with a refundable $1,000 deposit required to reserve a place in line. In order to land a reservation, people across the world waited for hours on lines to get into Tesla stores to pre-order the car. Some customers even camped overnight outside of a Tesla store in order to get the earliest possible reservation. Many of these people did all this before they knew what it looked like or key details such as the exact driving range.

Seeing if there were a sufficient amount of pre-orders was a make-or-break moment for the company. If there wasn’t enough demand for the Model 3 to produce it in high volumes, the dream the company had worked towards for over a decade would go up in smoke. Even if there were die-hard fans camping out in front of Tesla stores, there had to be hundreds of thousands of people who put down orders in order to justify the 3’s creation.

But Tesla’s dream wouldn’t die after that, because following the event the pre-order numbers were astronomical.

In the first 24 hours of availability, the Model 3 got 180,000 pre-orders. By the third day it had 276,000, and by the end of July they had surged to over 500,000 at an average selling price of $42,000 per car. For reference of how unprecedented this was for an EV, consider the following: the total amount of U.S. plug-in vehicle sales in 2015 (which includes both plug-in hybrids and EVs) was less than 120,000 vehicles, and 400,000 had been sold in the U.S. from December 2010 through the end of 2015.

One person who “put money down” for the Model 3 was iSchool physics teacher Thomas Smolka.

“I almost did [buy a Tesla],” Smolka said in an interview. “I needed to buy a pickup truck, because I just bought a house. I have this business that I have, I do things on the side and I needed a truck. I don’t regret the truck, but I really did want to get the Model 3. I actually put money down to get the Model 3, and then because of my changes in what I needed to do [I couldn’t get it]. I thought I was going to keep my old car and get the Model 3, but I really needed a pickup truck, so I went and bought the pickup truck.”

By this point, Tesla had already launched their Autopilot software, which would allow for automatic steering, lane changes, and parking, among other things. While not all of the pre-orders got the optional Autopilot upgrade, they all could later if they wanted to. That’s because Tesla announced in their presentation that every Model 3 sold would come with all the hardware necessary for Autopilot, and that any owner who bought a Model 3 without the software could later upgrade to it.

This was and is one of the main benefits of Tesla’s ability to update their cars’ software and firmware. While increasing performance or changing the look of the touchscreen is nice, being able to update the Autopilot software of a car that was sold years ago (and therefore improve it via newer and better algorithms) has become a strong selling point for their autonomous technology.

All this was coming soon. At the presentation, Musk stated that deliveries were expected to begin in late 2017. Just a month later, he set one of the company’s benchmark goals to be even more ambitious: instead of producing 500,000 vehicles per year by 2020, he said, Tesla would now produce that amount by 2018.

But by this time, Tesla was also looking beyond the Model 3. By June of that year, Tesla submitted an offer to buy another one of Musk’s companies, SolarCity, for somewhere between $2.5 – $3 billion in Tesla stock. SolarCity’s business model was based around installing solar panels for free, and then having customers pay a lease that was still less than they would pay for energy from the grid. They had also started getting into manufacturing these panels about two years before the deal took place. For this, SolarCity was working to build a factory in Buffalo, New York, that was approaching completion, and was slated to be the largest solar panel plant in the country when it was finished.

The acquisition proposal was highly controversial among Tesla stakeholders for three main reasons: first, in addition to being SolarCity’s chairman, Musk was also its largest shareholder, meaning he would get a large payout from the acquisition as Tesla bought his shares; second, the company’s co-founders Lyndon and Peter Rive were cousins of Musk, blurring the line between it being a business decision and a family matter. In addition to being the company’s co-founder Lyndon was still the company’s acting CEO. Third, the company was in a very bad financial situation when Tesla submitted the offer. The company had total long-term debt worth about $3.25 billion, which was even more than the high end of Tesla’s $3 billion offer. $1.23 billion of that debt was due by the end of 2017, meaning Tesla would have to pay for SolarCity as it ramped up Model 3 production. This has led some to speculate that the move was secretly a “bailout,” rather than a move to acquire a company and get into the energy generation space.

Despite the controversy, the acquisition talks went on.

By this point, Tesla had gone through all the steps of their master plan. They had released an early car with low volume production and a high cost, which helped paved the way for an even lower price car (that turned out to be two cars) which culminated in a car that was within the reach of the masses. They were also now getting into solar energy. With the master plan fully realized, Musk drafted a new roadmap for the future, which Tesla is still following through on to this day.

New Master Plan

“Master Plan, Part Deux” went live on the Tesla blog on July 20, 2016. Unlike the old plan, this new business model was less about how and why Tesla was doing what it would do for the future, and more about the specific markets it planned to get into and the products it would create for these markets. There were four markets that were laid out within this overarching scheme, and each was addressed in-depth.

The first market laid out was solar energy. Musk reiterated his support for the SolarCity merger, saying the two companies were a great fit – and claimed the fact they were separate at all was “largely an accident of history.” In addition to Tesla’s existing home battery, the combined entity would create what Musk called a “solar-roof.” This product would “seamlessly” integrate with the battery in a way that “just works,” allowing for “one ordering experience, one installation, one service contact, [and] one phone app.” This would then be “[scaled] throughout the world,” allowing people to generate their own power and be independent from grid energy.

Next, Musk laid out the details on the vehicles the company would create after Model 3. In order to most broadly address the consumer market, Tesla would create two new vehicles: a “compact SUV and a new kind of pickup truck.” In addition to these vehicles, Tesla would also expand beyond the consumer market, making a semi truck and a “high passenger-density urban transport” vehicle (by which he seems to have meant a bus).

In this section, he also describes his vision for the future of the company’s manufacturing:

“What really matters to accelerate a sustainable future is being able to scale up production volume as quickly as possible. That is why Tesla engineering has transitioned to focus heavily on designing the machine that makes the machine — turning the factory itself into a product.”

Treating the factory as a product, it would work to continually improve its manufacturing facilities, similar to how software is continually improved upon with updates.

The third point was that Tesla would further expand and refine its autonomous driving technology, and at some point would sell every Tesla with hardware capable of being fully autonomous. These vehicles would also have “fail-operational capability, meaning that any given system in the car could break and your car [would] still drive itself safely.” Musk stated his expectation that the main obstacle to conquer before self driving was available for the public would not be making it safe, but instead getting regulatory approval.

He also noted how the self driving system would get “better every day,” a likely reference to Tesla’s ability to analyze the driving of their cars through neural networks. Neural networks are a complicated topic that are tough to explain, so if you’re interested you can learn more about them in this explanation from MIT news. Musk also coined an argument for how the Autopilot software was safer than a human driver when it was “used correctly:” if one measures the average amount of miles it takes for a death to occur from a car crash, Tesla’s miles per death average with Autopilot engaged was much higher than the NHTSA average of miles per death from humans. This meant that it took more miles to be driven for an Autopilot fatality to happen than for a fatality to happen with a human driver, indicating that Autopilot is statistically safer. This conclusion has been somewhat controversial, with some casting the comparison as misleading.

Musk also pointed out the Autopilot software was classified as a “beta” (a title usually reserved for software that is functional but not ready to be released to the general public), and stated that the “beta” title would be removed once Autopilot was 10 times safer than a human driver.

Lastly, he outlined the most outlandish plan of any of the four – a fleet of what would come to be known as “robotaxis.” Essentially, once the vehicles could operate fully autonomously and without supervision, they could work as taxis and make money for their owner. If someone was busy somewhere, like at their job, they could press a button on the Tesla app and their Tesla car would automatically act as a sort of an autonomous Uber driver. The owner of the car would be able to make money from this because people would be charged for rides. This only made sense, he argued: “Since most cars are only in use by their owner for 5% to 10% of the day, the fundamental economic utility of a true self driving car is likely to be several times that of a car which is not.” Musk also pointed out the possibility that if a customer leased the car and made more money from the service than the lease cost, they could essentially have a Tesla for free.

In his words, the summary of the new master plan was:

“Create stunning solar roofs with seamlessly integrated battery storage

Expand the electric vehicle product line to address all major segments

Develop a self-driving capability that is 10X safer than manual via massive fleet learning

Enable your car to make money for you when you aren’t using it.”

More expansion

People wouldn’t have to wait long to see the plan start to take shape. On July 29, 2016 – nine days after Part Deux went live – Tesla held their “grand opening” of Gigafactory 1 in Nevada. The grand opening was the public’s first look at the constructed Gigafactory, and Musk gave a presentation further explaining how and why it was being built. However, the event was more of a grand showcasing than an opening, with the factory being a mere 14% finished at the time. But other parts of Musk’s master plan were much further along in their lifecycle.

In October 2016 – less than a month before a shareholder vote to decide the fate of the SolarCity acquisition – Musk unveiled the solar roof he had alluded to in his Part Deux plan. Instead of placing a solar panel on top of one’s roof, this panel actually is the roof itself, meaning it has more surface area and therefore can generate more energy. This also provided a nicer aesthetic, as there was no noticeable difference in texture between the roof itself and the solar panels. Just like Musk promised, the roof would integrate into Tesla’s pre-existing ecosystem, making the Powerwall, smartphone app, and solar roof allow for fully grid independent solar energy generation and storage. The roof would come in four styles: Textured Glass Tile, Slate Glass Tile, Tuscan Glass Tile, and Smooth Glass Tile, accommodating a variety of homes and styles. Musk also unveiled the improved Powerwall 2.0, which could both store and provide more energy to its user at any given time.

This event came 12 days after a previous announcement that if the SolarCity merger passed, Tesla planned to partner with Panasonic to make solar panels at SolarCity’s Buffalo factory.

When the SolarCity shareholder vote finally came, shareholders voted in favor of the controversial deal, which officially closed in November 2016. By early February 2017, the combined company announced it was phasing out SolarCity’s branding, and today all of Tesla’s energy products are sold under the Tesla name.

At the same time, that Tesla name also saw a change. Up until this point, Tesla’s legal name was Tesla Motors, Inc. But in addition to their phasing out of SolarCity, the company also shortened its legal name to just Tesla, Inc. This was done to reflect how they were now offering a broad range of products and services, and not just motor vehicles.

Also at the start of 2017, the Tesla Gigafactory began its life in a way that was practical rather than symbolic – it actually started making batteries. This was despite the fact that the factory itself was still undergoing construction. However, since that time, outward construction seems to have largely stopped, as images from drone flyovers show little change from early 2017 to now.

Once the Gigafactory began producing batteries, Tesla began preparing to produce the first Model 3’s and eventually to ramp up production.

But before any of that happened, they achieved a milestone many never thought possible. In April 2017, Tesla edged out General Motors (or GM) and became the most valuable car company in America. When it achieved this feat, Tesla had a valuation of $50.887 billion. GM is the parent company of Chevrolet, Cadillac, GMC, Buick, and a couple other brands.

Tesla’s newfound valuation raised some eyebrows, and many said the company was grossly overvalued. At that point, Tesla’s sales weren’t even a rounding error of GM’s – while Tesla sold 76,230 cars in 2016, GM sold over 10 million. This means that on average, for every car Tesla sold, GM sold over 131 cars. GM was also profitable – in 2016 Tesla lost $675 million in 2016, while GM saw a profit of over $9 billion.

But a few months after it hit its valuation milestone, the company completed a project that showed one of the more rational arguments in favor of it being worth so much – the potential of its energy business. While the company was preparing to ramp up Model 3 batteries, they made a record breaking singular battery for somewhere no one would’ve anticipated – Australia.

On July 6, 2017, Tesla announced that they had won a bid to make a large scale lithium ion battery. The battery would be near Jamestown, South Australia, to store energy for a pre-existing wind farm. South Australia had been hit by a 50-year storm and was facing massive blackouts, needing power quickly. Tesla’s offering was to be the largest lithium ion battery in the world, and would store enough energy to power 30,000 homes.

Since this was Tesla, it was only natural there was also an ambitious time frame that seemed aggressively optimistic when it was given. But this time, Musk attached an extra promise to show his commitment: not only would they make it in 100 days, but if they didn’t make it in time then the entire project would be free.

The public never got to find out if Musk was serious about his commitment, because Tesla built the battery with 40 days to spare. As of March 2020, it is still the largest lithium ion battery in the world, and Popular Mechanics has called it an “Undeniable Success.” A consulting group cited by Bloomberg said that the combined wind and battery saved the Australian government about $72 million in costs, which more than pays for the $66 million price tag of the battery.

July was also the month Tesla announced the addition of their first ever African-American board member, Linda Rice.

Beyond revealing their Australian battery and the addition of Ms. Rice to the company’s board, Tesla had another big moment in July when Musk announced that the first production Model 3 had rolled off the assembly line. By the end of the month, there was an event where the first 30 production Model 3’s were given over to their owners. It was a good showing for the company, and technically ahead of schedule for when they had hoped to get deliveries out – in the Model 3 unveiling, deliveries were said to start in “late” 2017.

But it wasn’t all good news. At the end of the event, Musk warned of the difficulties of ramping up production in order to fulfill pre-orders, and prepared for an oncoming “production hell” for “at least six months, maybe longer.”

He was more right than he probably realized.

In order to ramp up production and utilize true economies of scale, the company had to go through one of the most brutal and demanding times in its history, which would push everyone who worked there to the limit.

One great example of the difficulty in achieving what was desired for this is the scale of the battery increase. As previously mentioned, batteries are an essential part of electric vehicles, determining the range and also being the most expensive individual part to manufacture. In order to make the Model 3 production ramp happen, Tesla would need to make batteries on a truly gargantuan scale.

Per Electrek, the battery pack of a standard range Model 3 has 2,976 individual battery cells. If Tesla were to theoretically make 500,000 standard range Model 3’s per year, simple math dictates that they would need 1.488 billion battery cells a year.

Let that sink in for a moment: just under 1.5 billion. That’s an average of about 4.07 million a day, or 47.18 cells a second. And remember – that’s if they only made the standard range. A Model 3 long range trim, which they also sold, has 4,416 individual battery cells. More realistically, if 250,000 Model 3’s were the standard range and 250,000 were for the long range, that would bring the numbers to 1.848 billion a year, 5.06 million a day and 58.6 batteries per second.

And that’s just the batteries. Musk said the night of the Model 3 unveiling that “there are 10,000 unique parts in a Model 3.”

In essence, there was a lot of potential for things to go horribly wrong. But despite this, Musk was still confident Tesla could hit a production rate of 5,000 Model 3s per week by the end of the year.

His confidence did not serve him well.

“Production Hell”

Issues popped up as soon as the production ramp was attempted. The first sign of oncoming trouble was when one of Tesla’s suppliers “really dropped the ball” at the Gigafactory, according to Musk. Problems with the battery modules created massive problems that necessitated huge overhauls to the production process. Musk said that Tesla had to “rewrite all of the software from scratch, and redo many of the mechanical and electrical elements… of [battery] module production.”

What that ultimately translates to is this: Tesla produced only 260 Model 3’s in the third quarter, compared to 25,336 Model S and Xs (which, in a rare bright spot for the company, was a record number). That 260 was about a sixth of the 1,600 that were supposed to have been produced by that point.

Workers, who were not unionized, complained of oversight and negligence on the part of Tesla towards working conditions.

This would all come at a cost. Tesla lost a lot more money in the third quarter than it had expected to, at over $619 million in a single three month period. Musk pushed the 5,000 Model 3s per week deadline to the end of Q1 2018, instead of the end of 2017. He promised that Tesla would fix bottlenecks, and said there were no fundamental issues with the Model 3 supply chain.

Instead, not only would Tesla fail to meet analyst expectations in its upcoming production ramp, but new issues would be reported that shed light on just how bad the situation was getting.

The Wall Street Journal reported that parts of the Model 3 were being made by hand when they should’ve been made on the assembly line. Separate reporting from CNBC seconded that, and also indicated quality control was an afterthought. Oppenheimer, a financial services company, told Fortune that Tesla’s suppliers were late on deliveries, and that at least one supplier had been fired.

Despite all these issues, the company was still making preparations for its semi truck that Musk mentioned in the Part Deux Master Plan. In the midst of “production hell,” the Tesla Semi was unveiled on November 16, 2017.

To date, the Semi is the only commercial vehicle the company has shown to the public, and it did not disappoint. The truck would have four independent motors, and a range of either 300 or 500 miles depending on the model. Drivers would not have to switch between any gears, unlike traditional trucks that lose time switching between anywhere from 10 to 18 gears. It would be able to tow up to 80,000 pounds, and even with an 80,000 pound payload, the Semi was still expected to do 0-60 in around 20 seconds. It would also be much cheaper to operate than traditional trucks, potentially saving drivers tens of thousands of dollars per year. A little over a week after the unveiling, “expected” prices were released at $150,000 for the 300 mile model and $180,000 for the 500 mile variant. Overall, the Semi looked like a promising product, and by the end of the year it had pre-orders from household names like Walmart, Pepsi, and UPS.

Production and deliveries were said to start sometime in 2019.

It was a notable presentation, and once the stage lights dimmed, people reasonably started getting up to leave. But they would end up staying in their seats when a bright red light came on and a mysterious sound played – because it turned out Tesla had something else to reveal.

After showing off the Semi, Tesla dropped a bombshell by announcing a new Roadster was coming in 2020. And while the original Roadster was an impressive vehicle, the new Roadster, if Tesla could deliver, would shake up the high end auto industry forever.

The new Roadster would go from 0-60 in 1.9 seconds, making it the first car ever to do 0-60 in under two seconds. The car would also do 0-100 miles per hour in 4.2 seconds and a quarter mile in just 8.9 seconds. The car would have a top speed of over 250 miles per hour, although an exact speed was not specified. Any previous concerns about the range of one’s electric car would invariably be put to rest as the car boasted a 620 mile range. Unlike any other car with numbers that were even close, the Roadster had back seats, although it looks like there won’t be much legroom for full sized adults. The new Roadster would also feature a removable roof, making it the first Tesla since the original Roadster to do so.

Talking about why the Roadster existed, Musk said: “the point of doing this is to just give a hardcore smackdown to gasoline cars… driving a gasoline sports car is going to feel like a steam engine.”

The new Roadster started at $200,000 with $50,000 required upfront for a deposit. The first 1,000 sold would be founders edition Roadsters, which required $250,000 upfront.

Some have speculated that it is possible – if not probable – that the Roadster and Semi were unveiled as a sort of fundraising event, collecting money from pre-orders to raise cash for the company.

Regardless of the rationale behind the unveiling, both vehicles were exciting and had the potential to fundamentally alter their respective markets. This was great, but it didn’t change the fact that Tesla’s existing production was still a mess. Not long after the unveiling, Tesla’s Q4 2017 delivery results came out, and they weren’t much better than the quarter before. The company made only 1,550 Model 3s in the entirety of the fourth quarter, an infinitesimal number compared to the hundreds of thousands of pre-orders it still had. The 5,000 car per week deadline – which in the timeline of the initial Model 3 unveiling was supposed to have already passed – was pushed back to the end of Q2 2018. Now, a rate of 2,500 cars per week was expected by the end of Q1 2018.

The earnings results for the quarter reflected a similar situation. The company was still burning through cash at an unsustainable rate, losing $679 million in that quarter.

With how many things were going wrong, Tesla could use any form of good news at this point, and luckily they had some. By the end of the year, Model 3 reviews had come in, and they were overwhelmingly positive. Doug DeMuro, a highly popular car reviewer on YouTube, called the Model 3 “the coolest car of 2017.” Edmunds gave the car a 4.5/5, saying it “delivers many of the factors that make its predecessors so attractive, but at a much more accessible price.” MotorTrend, who had generally been fairly positive to Tesla, was particularly enthralled and impressed, calling the Model 3 “the most important vehicle of the century.” Michael Coren of Quartz, writing about other reviewers’ opinions, said “it’s hard to find a bad review.”

Throughout the first quarter of 2018, things started to get desperate, and the company was in dire straits. Production systems designed by outside suppliers weren’t working, requiring slower human workers. In a CNBC article, an anonymous employee had a worrying estimate: “40 percent of the parts made or received at [Tesla’s] Fremont factory require rework.” Throughout all this, it had huge upcoming debt payments – a $230 million payment due in November, and an astounding $920 million due in March 2019.

When Tesla reported first quarter figures for 2018, their financial situation was even worse than the previous quarters. The company had another quarter of record losses, at an eye-watering $784.6 million in a single quarter. The company’s cash reserves, which had been $3.4 billion at the beginning of the year, had dwindled to $2.7 billion. Tesla said they expected to be profitable in the third and fourth quarter of 2018 – but given how they were burning through cash and how widely they had missed other deadlines, this was hard for many to believe.

But there was also light at the end of the tunnel. As time went on Tesla started to get an idea of what was going wrong, and started working out some of their problems. By the end of the quarter, Tesla had made 2,000 Model 3s in a week, with just under 10,000 Model 3s over the course of the quarter. There was still a long way to go, but this was not a far cry from the 2,500 Model 3-per-week goal they had laid out for the end of the first quarter. It was certainly a lot closer to their goal in this quarter than it had been either of the two previous quarters, meaning they were on the right track.

But even if they were on the right track, they didn’t have a lot of time.

Throughout the beginning of 2018, the story began to spill into the mainstream, and the added scrutiny did not do the company many favors. While much of the focus was on the production difficulties, a fair amount was on the company’s finances and even long term survival probability – and it didn’t look good.

One particularly scathing report came from Bloomberg. The report estimated that if Tesla didn’t raise more money, there was a “genuine risk” that the company might run out of cash that very year. Bloomberg calculated that the company was losing $7,430 a minute. Much of this had to do with added payroll costs, as Tesla’s workforce had grown to nearly 40,000 employees in order to cover Model 3 production. While the company already had $9.4 billion of outstanding debt, many other analysts expected they would have to raise billions of dollars more cash just to survive the year, and billions more could be necessary in 2019.

The report also highlighted pressure from a recent crash that had taken the life of a Model X driver while the system was on Autopilot. A number of people thought it was misleading to label the Tesla system as “Autopilot,” and thought they should change the name to better reflect what the system can and can’t do. Some blamed the company for Autopilot-related fatalities, saying if Tesla made its capabilities clearer people who died using it would still be alive.

But automation wasn’t just causing problems in the car: it was also causing problems making them. As production went on, Musk eventually regretted his high utilization of advanced robots, saying that many of them were unnecessary.

“We had this crazy, complex network of conveyor belts … And it was not working, so we got rid of that whole thing,” Musk said in an interview at the time. “Yes, excessive automation at Tesla was a mistake. To be precise, my mistake. Humans are underrated.”

With the production ramp hemorrhaging cash and more capacity being necessary, Tesla did something that no one would’ve expected, and that might have ultimately saved the company.

On June 16, 2018, Musk announced that Tesla had built a tent with an assembly line outside the Gigafactory as a way to step up production capacity. According to The Verge, Tesla had previously said that once they stepped production up to 5,000 vehicles a week, they would stop losing money on every Model 3 sold, so increasing it to 5,000 vehicles a week as soon as possible was an absolute necessity. Jeremy Acevedo, at the time Edmunds’ manager of industry analysis, said of the tent: “We have seen automakers become nimble with their production, but not going as far as moving their production to a semi-permanent structure that I’m aware of.”

In the beginning of July, Tesla reported their Q2 vehicle production numbers, and it finally had the news stakeholders were hoping for. The report stated that “in the last seven days of Q2, Tesla produced 5,031 Model 3[s]… For the first time, Model 3 production (28,578) exceeded combined Model S and X production (24,761), and we produced almost three times the amount of Model 3s than we did in Q1. Our Model 3 weekly production rate also more than doubled during the quarter, and we did so without compromising quality.”

They had finally hit 5,000 Model 3’s a week. Tesla fans all around the world breathed a collective sigh of relief, as the company reiterated its previous position that it would be profitable in Q3 and Q4. It may have happened half a year later than planned in the 3’s unveiling, but it was on time relative to the revised expectations from Q1. The company was now on the right track, with it hitting its deadline showing a vital increase in the ability to make realistic schedules. While the statement that they achieved the milestone “without compromising quality” was questionable, given its opposition to statements from anonymous employees and some owners, the company still seemed like it was now in a more stable place.

The pain in getting there was not lost when Tesla reported yet another quarter of record losses: $718 million for the second quarter of 2018. However, while the past had been ferocious for the company, the future held much promise. Tesla said the gross profit margin on the Model 3 became slightly positive by the end of the quarter, and was expected to hit “roughly” 15% in Q3. This would be achieved by continuing to increase production, but now with experience in what not to do and more manufacturing capacity thanks to the tent. The company planned to focus more on making money and becoming financially sustainable, instead of ramping up production at all costs. While Tesla technically lost more money in Q2 than Q1, its cash reserves drained slower, ending at $2.2 billion by the end of Q2. This represented a $500 million decrease from the end of Q1 2018, significantly less than the $700 million decrease from the Q4 2017 to Q1 2018.

Also in July, Tesla announced plans to build a new Gigafactory outside of Shanghai, which would allow it to dodge import tariffs and more easily access the Chinese market. Musk stated expectations that the first cars would be created in the Shanghai Gigafactory within 2 years.

It’s important to note that through all this, the $35,000 Model 3 had never actually been delivered to customers. Instead, the company opted to build more expensive and more profitable trims of the 3, as the extra profitability would help offset Tesla’s losses. The Verge’s Sean O’Kane said the following about the approach:

“Tesla basically recycled Musk’s original ‘master plan’ approach. The company focused on building the highest-priced versions of the Model 3 first because they returned the most profit. If the company made the $35,000 version of the car too early, Musk said Tesla would “die.” The tens of thousands (or perhaps even hundreds of thousands) of customers who were waiting for the cheapest version of Tesla’s cars would have to wait, all while the federal EV tax credit slowly disappears.”