Children suffer the consequences of a non-accessible school system

November 7, 2018

Young Tayloni Mazyck was left paralyzed by a stray bullet from a gang shooting while waiting for her aunt outside her family apartment. Now she must use a wheelchair, and a nurse helps her at school. When she started to apply to high schools, she and her family made a prioritized list of schools ruling out all the schools that were not accessible, including many that matched her interests and talents. She was ultimately matched to a fully accessible school 70 blocks from her home.

The distance quickly became an issue because it was too far for Tayloni to wheel herself to school. As a result, she had to rely on DOE busing, which often came late or not at all. She had to leave class early due to schedule mix-ups with the buses. These, along with in school support issues, lead her family to withdraw her from school and pursue at homeschooling for her sophomore year.

In the months before her junior year, Tayloni and her family started looking for schools closer to home. They tried to find both fully accessible and partially accessible schools. Tayloni was also interested in three nearby charter schools but found out about them too late to meet their application deadlines. Other schools had wheelchair ramps in dark and isolated parts of the school, which raises safety concerns.

Tayloni and her family continued to sift through the DOE’s application and interview process, but given the lack of accessible schools that would meet her needs, she was unable to start her junior year on time.

Sadly, Tayloni is not the only child who has been abandoned by the school system; many children across the city are left with few options because of disabilities that they cannot control.

Marisa Luft, a sophomore at New York City iSchool, has seen for herself how kids with disabilities are treated in public school. Her younger sister was forced to transfer to a private school because a public school couldn’t accommodate her disability, “

According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), public schools are required to have the services to fulfill every child’s needs. Children with disabilities should be able to walk into any public school in the city and receive proper services.

When children are not getting the services that they need, families may hire a lawyer and sue the school for not following the law and making the school compensate for not giving those services to them. Depending on the case, they will get certain amounts of money that they will use to pay for a private school that can accommodate the child. These families are forced to sue the schools every year just to get the money to pay for tuition for private school.

However, many families cannot afford to hire a lawyer and are left with no option but for their child to suffer through not having accommodation for his/her/their disability.

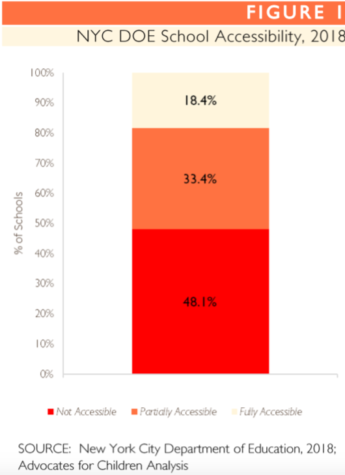

According to a government census done in 2010, there are 388,237 students with disabilities enrolled in New York public schools. And according to another more recent census done by Advocates for Children, only 18.4% of schools in New York are fully accessible. That leaves many of those children unable to get the services that they need to get the best education possible. The 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) forbids discrimination on the grounds of disability and mandates that both states and local governments must provide fair and impartial services that include education.

However, for many students with disabilities in New York City, it is incredibly challenging to find a school that they can access. In June of 2018, Mayor De Blasio and the City Council set aside $150 million over three years in the city budget to make the schools more accessible. Although this is a great step in the right direction, both have admitted that there is still much to be done.

In December of 2015, the U.S attorney for the southern district of New York found that the DOE is in violation of the ADA, or Americans with Disabilities Act, after an investigation of the accessibility of elementary schools.

Yet, twenty-eight years after the passing of the ADA and three years after the U.S attorney’s findings, schools still aren’t as accessible as they need to be. Children with disabilities are still left with limited options.

Because of the lack of actually accessible schools, the DOE sends parents in the direction of schools labeled as “partially accessible.” The problem with this is that the level of accessibility labeled as partly accessible varies greatly depending on the school. Many of these “partially accessible” schools have no accessible bathrooms or classrooms, others have limited elevator access, or rooms such as cafeterias, auditoriums, or libraries inaccessible to those who use a wheelchair.

Therefore, in a city that prides itself on education, in many students find that they cannot attend their zoned schools or even schools near them and they must travel long distances just to get to a school that they can access. Many students must forgo their favorite high schools, which forces them to prioritize accessibility over talent and interests.

Every five years the DOE develops a plan establishing funding levels for education-related projects, like new schools and school renovations.

During the fiscal year of 2015-2019, the plan originally included 100 million dollars over five years for school accessibility projects. While 100 million seems like it should be enough, it represents less than one percent of the funding in the 2015-2019 plan. As the U.S attorney noted the accessibility program for the 2015-2019 plan was nowhere near enough.

Mayor De Blasio recognized the plan’s flaws and, added 150 million over three years for school accessibility projects in the budget, which was adopted in June of 2018. The funding provides allows the DOE to continue making progress on school accessibility.

However, even with the added funding, the funding set aside for school accessibility still only accounts for less than one percent of the City’s 17.2 billion dollar budget for education for fiscal years 2015-2019.

Now, this fall the DOE will propose its plan for the fiscal year 2020-2024. While the city should certainly commit to making every school in the city accessible for everyone, the city should at least include a major investment to make at least one-third of the schools in each school district fully accessible to all students. It is estimated that in order to reach this goal the city would need to provide an additional 750 million dollars over five years.

There are three official DOE statuses for schools: fully accessible, as were mentioned earlier, partially accessible, and not accessible. The partially accessible schools are the school that does not meet with the ADA requirements, and these partially accessible schools vary significantly in terms of their actual accessibility.

Whilst the DOE is still in the process of rating the level of accessibility of these so-called partially accessible buildings, these ratings currently apply to the entire building and not the individual schools within a building.

the school that the DOE categorizes as “fully accessible” do not always meet the requirements for the ADA. In the DOE data 81 schools listed as “fully accessible” have a building accessibility score of 8 or 9 out of 10, meaning that a disabled person would have general access to all floors but have minor barriers or limited areas that are not actually completely accessible.

Most of these schools were listed as partially accessible as little as two years ago prior to the completion of building surveys.

However, given the wide variety of schools labeled as “partially accessible,” it is more important to focus on “fully accessible” as the primary metric for measuring school accessibility. While not all school that is labeled as “fully accessible” are actually fully accessible, it is still the closest indicator to families with disabled kids that a school meets or is close to meeting ADA standards.

According to the city’s data, there are 1,818 public schools across the city that are serving children from kindergarten to senior year of high school. This number includes both district and charter schools serving all grade levels, transfer high schools (transfer High Schools are small, full-time high schools designed to re-engage students who have dropped out or fallen behind in credits), and District 75 schools (these offers highly specialized programs for certain students with disabilities).

To combat the confusing varying levels of accessibility in schools labeled as “partially accessible,” the DOE has started releasing “ Building accessibility profiles” (BAPs). These BAPs give each school a score, on a scale from one through 10, for those partially accessible buildings and describe the accessibility for different parts of the building.

The DOE started using BAPs in determining the accessibility of high schools and now the DOE is working to survey the accessibility of elementary and middle schools. These BPAs take an important step in making the lives of disabled students and their parents easier.

Of the Cities 608 “partially accessible” schools 318 of them are schools with BPAs. the DOE is planning to conduct a survey of each individual school building.

Approximately 45% of schools that the DOE has labeled as partially accessible have a BPA rating of 5 or lower. These are buildings that, according to the DOE, may not include access to all floors in the building and may not have additional accessible bathrooms and/or classrooms other than on the ground floor.

Approximately 24% of the partially accessible schools have a BPA rating of one or lower. These means that the schools have no accessible bathrooms or classrooms.

According to the census done by Advocates for Children, fewer than one in five schools are fully accessible.

Citywide only 18.4% of the City’s 1,818 schools are fully accessible, and of the 1,483 schools that are not fully accessible 48.1% or not accessible at all and 33.4% are only partially accessible.

While accessibility varies from district to district there seem to be major deficiencies in the vast majority of districts across the city. In 28 of the city’s 32 districts less than or-third of the schools are fully accessible and in seven of the city’s 32 districts, less than 10% of school are fully accessible.

In District 16, covering most Bedford – Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, there are no fully accessible schools at all. There are three districts (12,16 and 21) that have no fully accessible elementary schools, four districts (7,14,16, and 32) that have no fully accessible middle schools, and six districts (14,16,18,20,21, and 32) that have no fully accessible high schools.

Although There may be a higher percentage of high schools that are fully accessible, some are still unavailable to students because of their admission criteria. Of the 145 high schools that are fully accessible, 32 use highly selective admission methods – i.e, tests, auditions,etc.he admission methods remove 22% of the fully accessible options for any student who cannot meet the criteria.

However, students who do meet all of the criteria for the very selective high schools and who need full accessibility school have limited options. Only 38.6% of the 83 schools that use these highly selective admission methods are fully accessible.

The city has a severe shortage of accessible schools, but the problem is prevalent mostly in elementary and middle schools. The shortage of accessible schools in these younger grades means that too often young students are forced to go out of their way and travel long distances just to get a decent education.

Only 16.2% of 1,015 elementary schools are fully accessible; only 18.2% of 665 middle schools are fully accessible, and only 24.6% of 590 high schools are fully accessible.

The DOE operates 60 specialized for students with disabilities known as District 75. The schools are designed for students who need more intensive special education programs than the District 1-32 provide. While not all students that are recommended for District 75 have a physical disability, some students are recommended because of significant cognitive disabilities.

A single District 75 school may have classrooms in several different school building with sites in different districts, serving different grade levels, or specializing in catering to the needs of certain disabilities.

As of the summer of 2018, the 60 specialized schools they are a part of District 75 operate out of 382 building across the city, and across all of these buildings, there is a shortage of fully accessible schools.

Out of these 60 District 75 schools only 11 (18.3%) are fully accessible and of the 382 buildings that the District 75 schools occupy only 103 (27%) are fully accessible.

While a small number of the 273 charter schools in New York rent or own their spaces, the vast majority are located in buildings operated by the NYC Department Of Education. As of the summer of 2018, 14 charter schools occupied privately owned spaces and their accessibility is not yet assessed, therefore, they are not included in the following data.

Only 26 out of 223 schools, charter schools have a lower percentage (11.7%) of fully accessible school then DOE direct schools (19.6%).

Likewise, a higher percentage of charter schools have buildings labeled as “not accessible” (67.3%) than DOE district schools (44.9%).

At every school ever there is a smaller percentage of fully accessible charter schools then DOE district schools. Elementary schools : 11.8% vs 17.2%, middle schools: 14.3% vs 19.6%, and high school: 17.8% vs 26.4%.

Even though NYC charter schools began opening in 1999, nine years after the passing of the ADA, most of the charter schools have opened in schools that are not fully accessible. Thus, while the key purpose of charter schools is to provide choice, they actually limit the options of families with disabilities.

the best way to ensure that students with physical disabilities actually have equal access to public education is to ensure that 100% of schools in New York City are fully accessible. In light of the upcoming FY 2020-24 DOE capital plan, it is best that the city commits to making at least one-third of schools in every district (including district 75) fully accessible. Currently, 28 out of 32 districts fall short of this threshold.

Ben Champman, a reporter for the Daily News said that “When a student is misdiagnosed or denied services then they encounter a number problems with social, academic, behavior has a ripple effect into adulthood.”

So in order to avoid more disabled students like Tayloni, and Marisa Luft’s sister being left behind by the school system, the city should ensure that any space rented or purchased by the DOE meets the standards of the ADA before using it as a school space. Until 100% of school in New York are fully accessible, the DOE should provide additional assistance to families with accessibility needs in the admission process, like priority tours, and putting more importance on admission requests would help to make the process more equitable and that every student is getting the best education possible.